>>>Join Phaidon and MOLD at the New York City launch of On Eating Insects. A celebration of entomophagy, we’ll be screening the award-winning documentary film BUGS and have a book signing with co-author Josh Evans. Saturday, April 8th 11:30AM – 2:30PM at the Ace Hotel in New York City. Grab your TICKET HERE.<<<

It’s a chilly winter day and Roberto Flore has released the insects in my Brooklyn kitchen. Flore, the head of research and development at NOMA’s famed Nordic Food Lab, is in town to meet with collaborators and he’s brought an arsenal of flavors with him from his Copenhagen kitchen–wax moth larvae garum, ant gin, hornet moonshine, roasted palm weevil larvae. But these buggy snacks and sauces aren’t just for observation; Flore is a champion for entomophogy, eating insects, and this spread is just a peek into the Lab’s upcoming book On Eating Insects, a collection of recipes, essays and stories gleaned from years of travel and research.

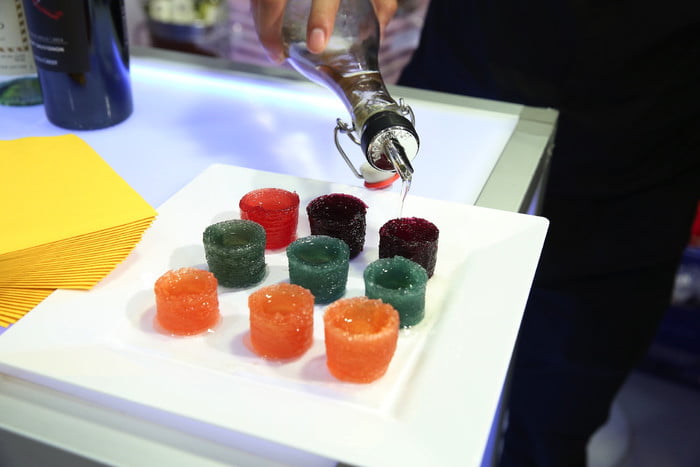

Bee Bite. Image courtesy of Chris Tonnesen

Bee Bite. Image courtesy of Chris Tonnesen

Established in 2008 in Copenhagen, the Lab was founded by Rene Redzepi and Claus Meyer to investigate the full gastronomic potential of Scandinavia. Through a collaborative environment, chefs, scientists, anthropologists and artists probe the complexity of eating through the lens of local sustainability informed by global methodologies. Ahead of his presentation on the future of food at the Nobel Week Dialogue, Flore spoke to MOLD about his research process, the Nordic Food Lab’s mission and why eating insects and jellyfish can create economic opportunities. Below are excerpts of our conversation as told by Flore.

How the Production Chain is Limiting What We Eat

At the Lab, we take a complex view on sustainability and how it relates to the way we eat and how we perceive the place where we live. In the last 50 years, the human diet has evolved by cutting out so many things. For example, we don’t consider insects as an edible source of food—this perspective cuts out an ingredient from our diet. People are scared and in some cases, have lost knowledge around using certain things. For example, foraging wild herbs or using unusual cuts of meat like guts or the brain.

Reviving Old Techniques for the Future

We research techniques from around the world and bring them back to Scandinavia in order to build up a more complex approach to our products. One example is garum, an ancient Roman sauce made with fish guts and salt. Basically, it’s a centuries-old recipe for fish sauce that was used throughout the Mediterranean. We wanted to create a fish sauce or something like a soy sauce with 100% Nordic ingredients.

Hornets, gingko fruits, and mitsuba (Japanese wild parsley), for a chawanmushi experiment, Japan. Image courtesy of the Nordic Food Lab

Hornets, gingko fruits, and mitsuba (Japanese wild parsley), for a chawanmushi experiment, Japan. Image courtesy of the Nordic Food Lab

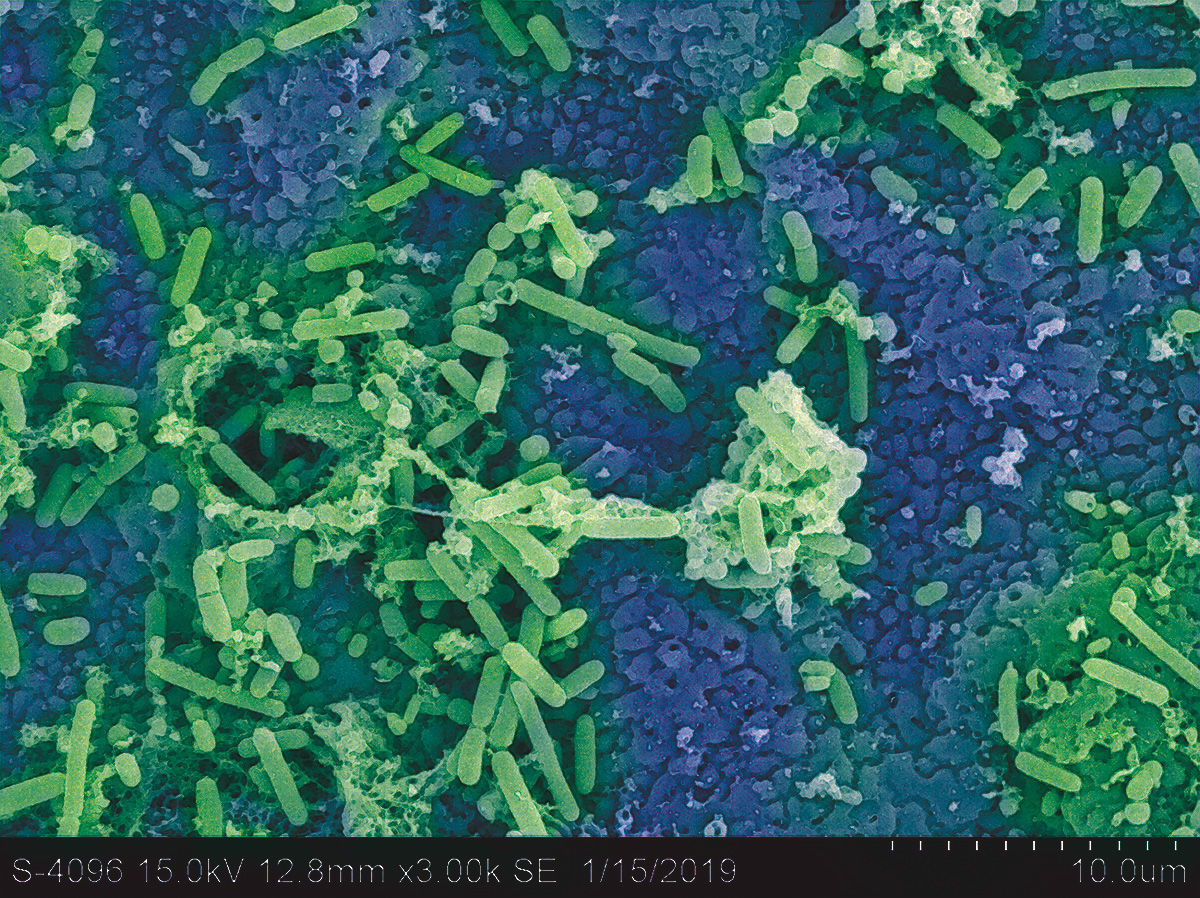

We studied Japanese production methods and began growing koji on barley because in Scandinavia, its much more common to have barley (not rice). And because we don’t have soy, we switched the protein content of soy with the protein content of insects and then we ferment it. We succeeded in creating a product that is true to our landscape but it’s inspired by an ancient technique from abroad. Using this approach, we’ve designed a lot of products in the Nordic Food Lab.

Food Culture and Open-Source

We are an open-source organization and our goal is really to disseminate as much knowledge as we can because by sharing this sort of knowledge, you really keep alive thousands of years of human history as it’s related to gastronomy. That is why we keep traveling and meeting people, putting the culture in front of everything. If people eat an ingredient, there’s a reason for it. We ask “why” and “how” and if we can keep this approach when translating it to our region.

Specimen samples from fieldwork in Australia. Image courtesy of Chris Tonnesen

Specimen samples from fieldwork in Australia. Image courtesy of Chris Tonnesen

Related to this, we always try to create a situation where the way we interact with food also changes the way you interact with people because you recognize a food culture. You recognize the food culture and the people behind it so you’re more open to an ingredient that might look completely weird or uninteresting for you—it becomes a taste of a delicacy from another person.

Eating Invasive Species

How can we transform a problem into a resource and also stimulate the growth of new markets while rebalancing the ecosystem? One big sustainability project we’re working on is researching seaweed and jellyfish. In the Mediterranean, jellyfish are invasive. It’s a huge problem for everyone from small fishermen to large fishing companies. We might see jellyfish as a pest, but in many places in Asia, it is a delicacy. The ecosystem there is completely destroyed by overfishing and we’re trying to create an economic alternative that could rebalance things. Fishing jellyfish, an aggressive species that is reproducing exponentially, also opens up the possibility to fish less and in a more diverse way.

Fin to Fin Cooking

As with everything, we’re encouraging chefs to use all the cuts. As a chef, when you buy a fish, you throw aways serious money when you toss the guts and the bones. Why not buy the highest quality fish and use all the parts? At that point, you can have a real signature in your dish. Instead of seasoning it with commercial fish sauce, why not make your own? By making this type of knowledge available, it will bring gastronomy to a level of reflecting 100% of what’s happening, on the plate.

Bee Larvae Taco. Image courtesy of Chris Tonnesen

Bee Larvae Taco. Image courtesy of Chris Tonnesen

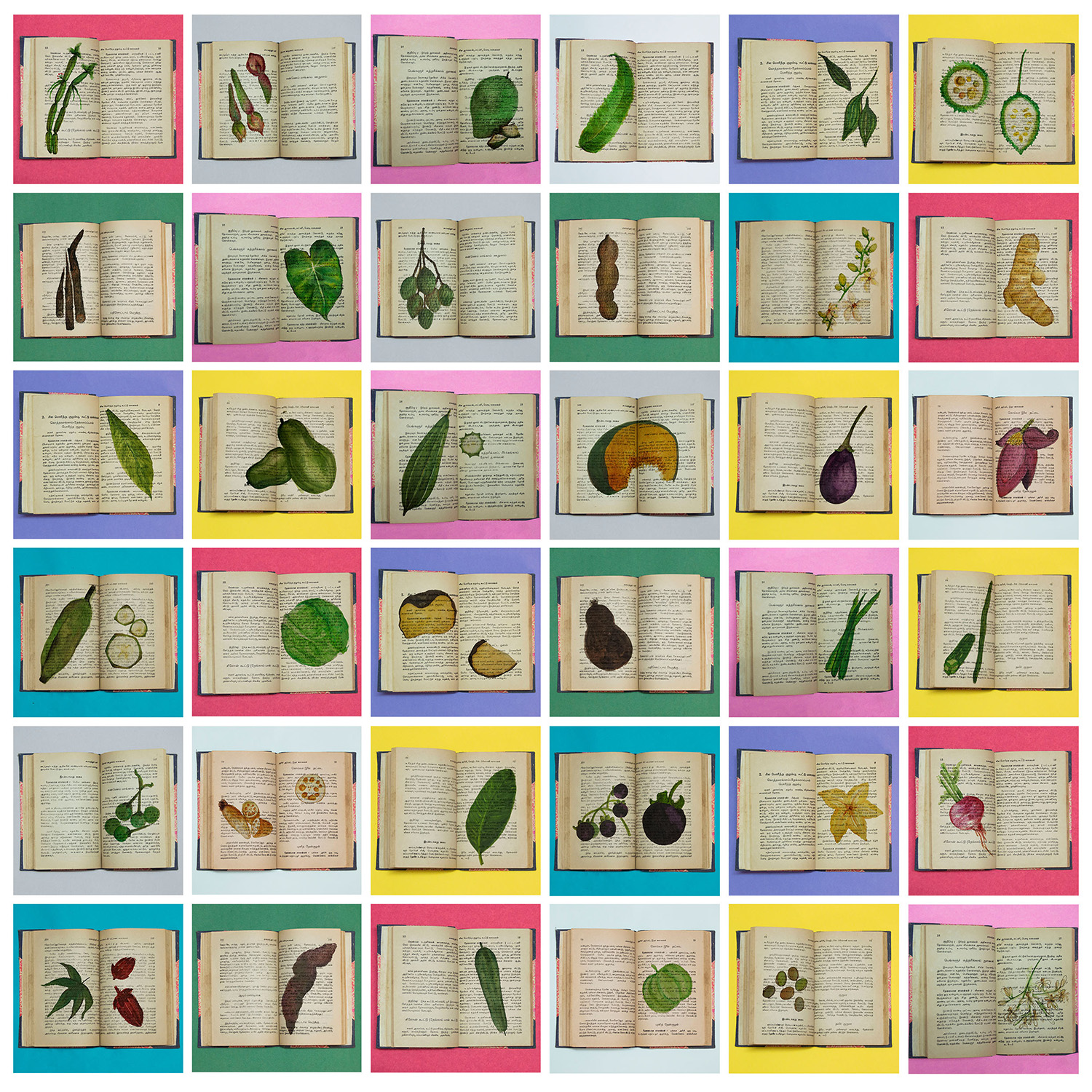

Tempeh Innovation

Over the last 40 years, tempeh production has become industrialized in Indonesia. As the industry grew, imports of soybeans also increased—today 70% of the soybeans use for tempeh and tofu production is imported. Traditionally, tempeh production is diverse—you can use different grains, different beans and use wild strains of mold—and there is a diversity in taste. Now, there’s a huge loss of biodiversity in Indonesia because tempeh is becoming standardized with imported GMO soy and a standardized fungi starter.

We’re working to address this in two ways. The first is to share the results from our tempeh research to encourage chefs and the market to work on local products with innovative techniques of production. We want to build a context where people perceive local beans as more valuable, therefore paying more for high quality local products. We were researching in the area southeast of Java, visiting different local producers there. It’s really impressive because traditional tempeh production is small-batch and very specific. For example, the velvet bean takes five to seven days because you have to soak the beans a few times to remove the poison—it’s really hard work. Instead of producing a few tons of beans in an industrial facility, traditional producers only make 20-40 kilos a day. It’s also really necessary for local farmers to organize to supply the quantity and quality of beans that are necessary for production. Farmers need to trust the quality of their products more and chefs and the world of gastronomy can help lay the foundation for this.

Koji experiments at the Nordic Food Lab.

Koji experiments at the Nordic Food Lab.

Back in Europe, we’re working on developing new recipes, applying different tempeh strains and molds on local grains and seeds. We’re even collaborating with El Celler de Can Roca in Spain to develop interesting techniques to use all the enzymes that are produced after the fermentation of tempeh. Within a local context, tempeh is perceived as the last part of production, the edible product. But for us, it’s just the starting point of something else. At that point, we succeed in creating something completely new and different from what is happening in the local context.

Collaborating for the Future of Food

How can we work together to make industrial production better? As chefs, we often see industrial production as the devil. Working within a university context offers us the possibility to connect directly with future food technologists. We want to create a more empathic, holistic approach to industrial products. We want to change the way that future food technologies interact with future products, giving them a more complex understanding of what food is through culture and not just chemistry.

Suri juanesitos (palm weevil larvae), Peru. Image courtesy of Nordic Food Lab

Suri juanesitos (palm weevil larvae), Peru. Image courtesy of Nordic Food Lab

A simple example is bread: you can make bread that lasts a week by adding a lot of additives or you can make sourdough which is full of flavor too. We can teach these food technologists to look beyond just the shelf life of a product and work on the flavors and everything can come back around full circle.

We want to create an interactive environment and vibrant collaboration to change our perception of food. Working with artists, food technologists and chemists can build towards a more complex interaction for those working on food from different angles. We are trying to undermine industrial production by centering people who are more conscious while also building awareness amongst customers about how food should be and the complexity of sustainability. Chefs can’t do everything—everyone needs to do their own part.

On Eating Insects by Roberto Flore, Josh Evans, Michael Bom Frøst and the Nordic Food Lab is out May 1st from Phaidon. Pre-order your copy here.