The artist and designer Allie Wist was working in the trenches of New York City’s notoriously competitive food media industry when the crush of climate change creeped into her consideration. New York City was still grappling with the devastation wrought by Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and concerns about coastal flooding, rising sea levels and the resiliency of our cities regularly peppered news headlines. The question of how and what we would eat in the future, despite coastal flooding and sea level rise, became the seed for Flooded, a research project and accompanying cookbook—or “gastronomic science fiction,” according to Wist.

Since its launch last year, Flooded has traveled to various locales in a number of forms—a lecture series, dinner, and photo show—and with its success, the team behind the cookbook is ready to explore a new phase of their project with Drought, now funding on Kickstarter. The new project will focus on drought-resistant ingredients like jackfruit, cactus and certain heirloom grains. You can support the research and photo production by backing the project today!

MOLD: What was the initial inspiration for the Flooded Series? Why photography?

Allie Wist: Flooded was initially inspired by Marinetti’s Futurist Cookbook, which was a performative exploration of food, published in 1930, as a means of communicating ideas about culture in Italy at the time. I asked myself what a new “Futurist” exploration of food would look like—what would the new values be that we should communicate through food? I felt strongly that it should communicate a way of eating that was more connected to our environment, and one that focused on eating sustainably in light of climate change’s effects on our food system. If there was an urgent message to tell about food, that was it.

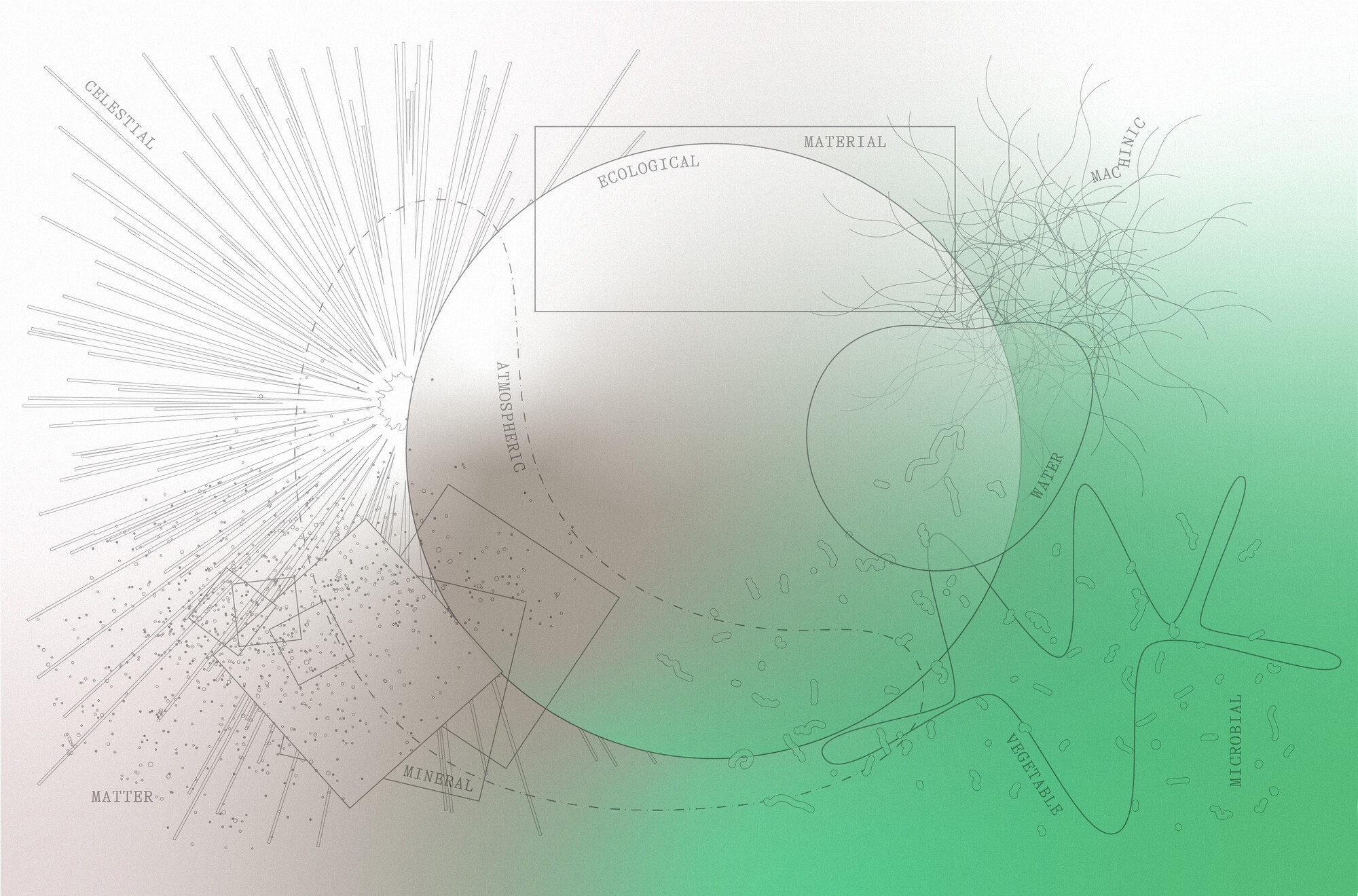

I had been simultaneous really interested in Sea Level Rise maps of NYC, and how many urban areas were under an ominous swath of blue when you raised the sea level even a couple feet. A fellow artist and I started writing prose about what eating would be like, despite coastal flooding and sea level rise, which helped spur an idea to create a more personal visual narrative related to sea level rise.

I steered the project towards photography because I think food photography is a format that has incredible cultural potential right now—people are highly interested in food both conceptually and practically, but much of the food photography in the media is not used for activism purposes. I wanted to repurpose the language of high-end editorial food photography to tell a different story. The women I collaborated on this project with all have worked in food media in New York City, and we were all passionate about creating a sort of gastronomic science fiction and setting forth a new visual language for “sustainable” eating.

Where has the project traveled and in what formats? How has it been received differently based on geography?

The ways that the project has been received in different areas around the world has been really interesting and has, in fact, helped to broaden the project’s scope. In Finland, I gave a keynote about the photographs, and the audience was the most interested in our inclusion of foraging—that was a very familiar concept to them, and they gave some great insight about it’s potential for reducing some of our reliance on a global (fossil-fueled) food system. At another speech in Iowa, I had some pushback about the project’s implicit criticism of industrial agriculture. I got into an interesting conversation about where “big ag” and the sustainable food movement could meet halfway in the future—could drought-resistant crop varieties be shared in an ethical way with farmers experiencing climate change-caused drought?

This month we also installed 13 of the photographs with Honolulu Biennial in Waikiki and expanded upon the concept. Locals in Hawaii really embraced our use of seaweed, as that is something that they already use in their cuisine extensively and creatively. They were really the seaweed experts, and we learned a lot from them. We went and foraged for invasive seaweed at a local fish pond and pickled giant jars of it in the gallery. All 24 jars are now on display in the gallery as part of the installation. It helps to tell a local story about the importance of utilizing invasive edible plants.

What are some of the unique ingredients/processes you focused on for Flooded? Why?

Ingredient-wise, one thing we really focused on was seaweed. This was inspired, in part, by the work of Bren Smith at Greenwave, who incorporates kelp into a sustainable ocean farming model. Kelp has the ability to absorb up to five times as much CO2 as land plants, and doesn’t require land, fertilizer, or fresh water. It’s a low-cost, potentially high-reward crop that helps to restore the health of our ocean ecosystems. We also incorporated bivalves, like oysters and mussels, which have been proposed by scientists as the most ethical seafood choice we can make. They are filter feeders, which means they can actually filter our waters, and structures like oyster reefs have traditionally been important for protecting coastlines from storm surges and flooding. Several of the plants that Buckley chose, like burdock, dandelion, and chickweed, grow wild in New England and can help infuse ideas about biodiversity back into our food system.

We also focused on some broad techniques that we see as important to our future food system. The food stylist (CC Buckley) and I wanted to emphasize the importance of preservation as a way to use seasonal produce, as opposed to having our strawberries flown in from South American in the winter. Values related to thrift and waste reduction were important too—Buckley included a stock in the recipes as a representation of utilizing ingredients that may otherwise go to waste. We also liked the concept of foraging, as it helps to encourage an intimacy with our environment that most urban eaters don’t get. While the realm of food future “tech” is a valid one, we focus more on how innovations from our past could play into our future.

With Drought, what are some of the ingredients/processes you’re excited to work with?

We already have ideas for both the visuals and the food—our prop stylist, Rebecca Bartoshesky, has had desert-themed backgrounds and textures picked out for months!

As far as food, I am hoping to incorporate breadfruit, which is this amazing starchy “fruit” that is incredibly nutritious, and a fairly hearty, drought-tolerant plant. The chef we worked with in Hawaii, Mark Noguchi, really got us excited about it. You can cook it similarly as you would a potato, and it’s delicious. We will look at other drought-tolerant edible plants, like cactus and certain heirloom types of squash, as well as agave and yucca. I am working with a climate scientist at MIT, who has recommended sorghum as another potential alternative grain, as well as helped me navigate the variability in agricultural forecasts. Buckley is an herbalist, so we’ll also have themes about our beneficial relationship with plants and ethical wild-crafting.

Support Wist and her collaborators through their campaign now funding on Kickstarter.