Imaginative and innovative approaches to food have long been brewing in the Basque Country in northern Spain. The two Michelin-starred restaurant Mugaritz, considered one of the top restaurants in the world, is an engine for creativity and “techno-emotional” cuisine. In October 2016, I sat down with the Chef Andoni Luis Aduriz, the head chef of Mugaritz, and Chef Dani Lasa, responsible for the Creativity + Research team at Mugaritz, to discuss the personal and social dynamics of food technologies and fine dining and how their approach to pushing their audiences’ mental boundaries influences culinary culture outside of the confines of a fine-dining institution.

Chefs Andoni Luis Aduriz (left) and Dani Lasa (right) of Mugaritz (Photo by Vicky Zeamer)

Chefs Andoni Luis Aduriz (left) and Dani Lasa (right) of Mugaritz (Photo by Vicky Zeamer)

Vicky Zeamer: What should we understand about the relationship between food technology and culture?

Andoni Luis Aduriz: Technology is like a magnifying glass. It is a tool that amplifies what you want to cook. If you put a magnifying glass on a shit, it makes the shit bigger and if you put it on a flower, it makes the flower bigger. So, in the end, the technology is only a medium, but it is an amplifier. There are individual or professional cooks, who with technology are worse or with technology are better, but it does not depend as much on the technology as on the hand that uses them.

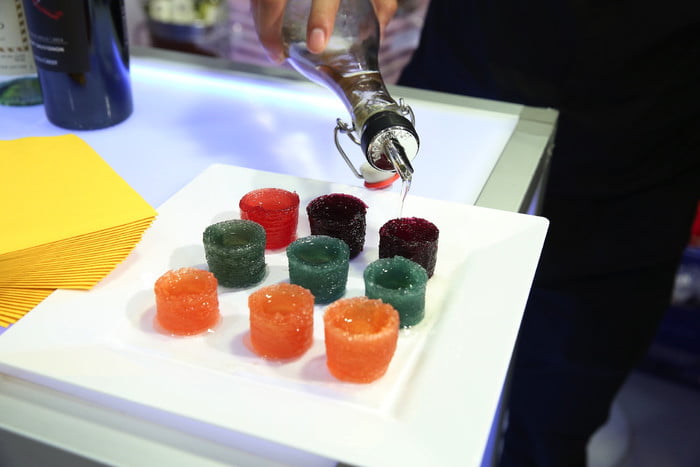

Sun-ripened berry fruits, drops of extra virgin olive oil, lime and cold beetroot bubbles.

Sun-ripened berry fruits, drops of extra virgin olive oil, lime and cold beetroot bubbles.

When your team came to MIT in 2014, it was discussed that judgment is strictly linked to prior knowledge of the food texture, color, shape or other physical attribute. Many of your dishes are famous for subverting or changing these judgments, and making old foods with new ingredients such as the watermelon carpaccio or the cheese made from the milk skin of linseed. What lessons have you learned from this practice and what do you think it has to say about people in their approaches to new foods?

Andoni: When we try to do something, somehow in your head there are no such questions [like what people will like or not like]. Instead, we start from the fact that we are trying to build an experience. We deal with the reality that we are carriers of a knowledge that we are trying to share and that knowledge, in the end, comes from exploring all possible forms of matter. When you have an open mind, you are discovering things and those that you consider the most interesting you try to share with the client. It is very exciting to know that people discover things that they would not have even imagined they could discover. And many times, you put them in front of their own limitations, because there is a paradox. On one hand our mind is very conservative, but on the other hand, it is also very curious.

Then, it depends on each individual, there are people who enjoy discovering and there are people who suffer discovering. So, it’s true that in the whole process, we always have the idea that the cuisine makes the guest more creative. Many new things are derived from this creativity. Because when you try to make a creative cuisine you can discover new textures, new elaborations, new ideas, new concepts, sometimes you can apply them to different areas. If it happens that one day you have to do a project for the elderly, you discover a little of what they face, what problems they have. Many times you realize that something that you do in a natural way can serve to change textures, enrich textures. If you do a project about food and children you realize that many of the things you do, can also be used in a project of these. But the starting point is that we try to make people more creative. Okay, and that’s how we ask questions and the answers we present to the guest. This is the beginning, what happens is that it is true that you handle so much information at the end.

Dani Lasa: We would like to take more advantage of all that knowledge because, actually, we are serving a limited amount of people, to a thousand people, is not transcending but, yes, you want to use your knowledge for all these differing and further reaching purposes.

Do you have any plans to try to use or consolidate that knowledge?

Andoni: Well we can talk about concrete projects, everything we have done with Healthouse, for example, has been based very much on the empiricism we have worked on in the restaurant.

Lasa: We’ve been involved in research projects for elderly people, gerontology [Healthouse]. We’ve been working with some hospitals and food companies. Although, maybe the rules and the strategies they manage are not the ones that we support, but they asked us to develop some gastronomy menus so the people that was going to that hotel were not going to lose the opportunity to enjoy leisure and gastronomy or good vacations. But, our limit was to not surpass 700 calories per menu. So, we have developed 10–12 courses long menus with lower calorie content than 700 calories. You are somehow forced to learn about a lot of things, how your palate works, how your brain works, how your gut works, so we cannot apply it in just one person, we need to find all the ways to apply it, as you say.

Another project was a Spanish project involving gerontology, hospitals, food companies, ingredients companies, so we were part of a consortium of 12 companies [and have been involved for] five years with this cause. We think about how we can apply all the knowledge, because some of it may be useful and it could be a business model, and then it could be transcended to greater society.

What do you think are some of the most interesting examples from learning about people’s palates and what they will and want to eat?

Andoni: The senses are windows, they give information, but the most interesting thing is the way people interpret that information. In the end, we see as we have been taught to see; we listen as we have been taught to listen; we taste as we have been taught; “This is good and this is bad” is installed in the mind.

There is a biological part, there is a cultural part, and there is an affective part that is in the middle. So the first function of the brain is to protect us. The brain evaluates by comparison—there’s a great mismatch because we forget that eating has been risky for millions of years but today, we no longer evaluate it as risk, but our brain still does. Because the brain knows that eating is dangerous, it will handle two concepts that are pleasure or disgust, so that you eat what it considers to be safe. So what’s the first safe food you’ve eaten? It’s your mother’s or your grandmother’s food. Then the brain identifies: safe food.

Also there is the affective, the symbolic. Once you have been given a key to open a door, you will be able to open the door that you had unopened. Every culture has a key; this is the way to understand the food complexity of the place. Besides the food, it is also the symbols that matter as well. In the Basque country, for example, we eat codfish chins, not so often we eat baby eels, or we can eat squid in their ink—for us, any of these three products are excellent. Someone from Boston comes and eats the codfish chins and goes to say, “This is very gelatinous, it’s disgusting,” sees the baby eels says these are a worms, and sees the squid and says he would never eat that. But in the Basque country, we open it with our own key. You go to Mexico and you eat escamoles, you jump to the Philippines and what they give eat the balut, and you go to the Amazon and you eat the turu, which are like worms. For each culture the food of the rest of the world can be disgusting.

Your mechanism of protection is disgust and it lies in the area of the insular cortex of the brain; it is illuminated with disgust over food and with social disgust. When you say, “wow, Donald Trump makes me sick,” it turns on the same area of the brain as when you see worms. Because when you see worms and they are not part of your culture, the brain identifies that there may be a very big risk. When you see a person from another culture, another race or another clan, [your brain can identify that person as someone who] could bring diseases that could infect you. That is why the same area of the brain is turned on.

Pleasure is the opposite, I will give you pleasure so that you eat what I know will serve you. From the point of view of creativity, knowing that today we have to fight against what is installed in the brain, the dream would be that the key that we all have will open all the doors, such as a master key.

Have you come close to finding some way to unlock that door?

Andoni: We have come to something close to that. Look at Mugaritz; people come from all over the world, people of more than 70 nationalities and know that we are not going to make it easy for them. And in fact it’s very curious, because a lot of people say: I have things that I usually do not like but I come here willing to try them.

Lasa: So maybe our biggest success is having them be aware that we are going to do it [in a way that is] not that easy, we are not going to cook just for pleasure, but for other challenging exercises. So you somehow change their predisposition in order to take risks, because they know they are in your hands, and you will push them beyond a little bit.

I’m interested in how we can learn from fine dinning. Typically, when people go into fine dining restaurants, as you discussed, they are ready for that change. So, how do you think that the innovation and experience design being developed within fine dining can spread outside of the restaurants?

Andoni: Well, it’s happening. It is actually an exercise in pedagogy. You have to realize that there are some spaces, these restaurants models, which have been created for and are available for an audience that really wants to explore. And that repeated, in time, will penetrate different levels of society.

We can see examples from our closest environment—if you take a look at the dishes that my mother made at home in traditional Basque cuisine from the ’50s or ’60s, with a recipe like merluza in green sauce the name has not changed but now all the concepts of high cuisine are being applied to the traditional recipe. For example, before, the fish was cut into slices, but high cuisine made people remove the bones. Traditionally the fish was cooked in a lot of sauce which loses the taste. Today a smaller vessel is used just for the sauce which goes directly onto the plate. When cooking the fish, the heat is filtered little by little and it is seasoned before—in high cuisine you do not exaggerate, if you season the fish 20 minutes before cooking, it dissolves the salt and stays on the surface of the fish to prevent the loss of collagen. That recipe has nothing to do with the recipe of the ’60s. And all that has passed from the high cuisine to the home. That happens with a lot of things. Today, for example, breads have less salt. Today people are asking for breads with much more sensorial characteristics. It has raised the level of demand and also the level of health. So much of the high cuisine ends up getting popular.

I’m also interested in when people talk about food being natural, that’s also a sort of construction we have?

Andoni: It’s a distortion. Look, people interpret the natural cuisine as the cuisine that comes from nature, that which comes without intervention. And there are products that are natural, that is, we pick them up from the ground, but almost everything we eat is the result of human interaction with nature. An apple is not a natural product, a tomato is not a natural product, corn is not a natural product. They are cultural products because in nature, they do not exist as we know them. This is what people confuse. Basically, behind agriculture there is a lot of technology, but we do not realize it. Actually what people mean is “healthy.” Curiously, the natural can be healthy or the natural can be unhealthy. People should learn to use the words natural and healthy.

You’ll go to the store and the food will say “All Natural,” but what does that mean?

Andoni: It is a very ambiguous term. But if people knew that almost nothing that they consume is natural they would surely be surprised. For example, fish is a natural product as we continue to fish from the water as we did in the Neolithic, some types of mushrooms that are collected wild and unaltered, and then some types of asparagus and wild fruit are the same, but everything else is intervened.

What are you looking forward to in the future of Mugaritz and food?

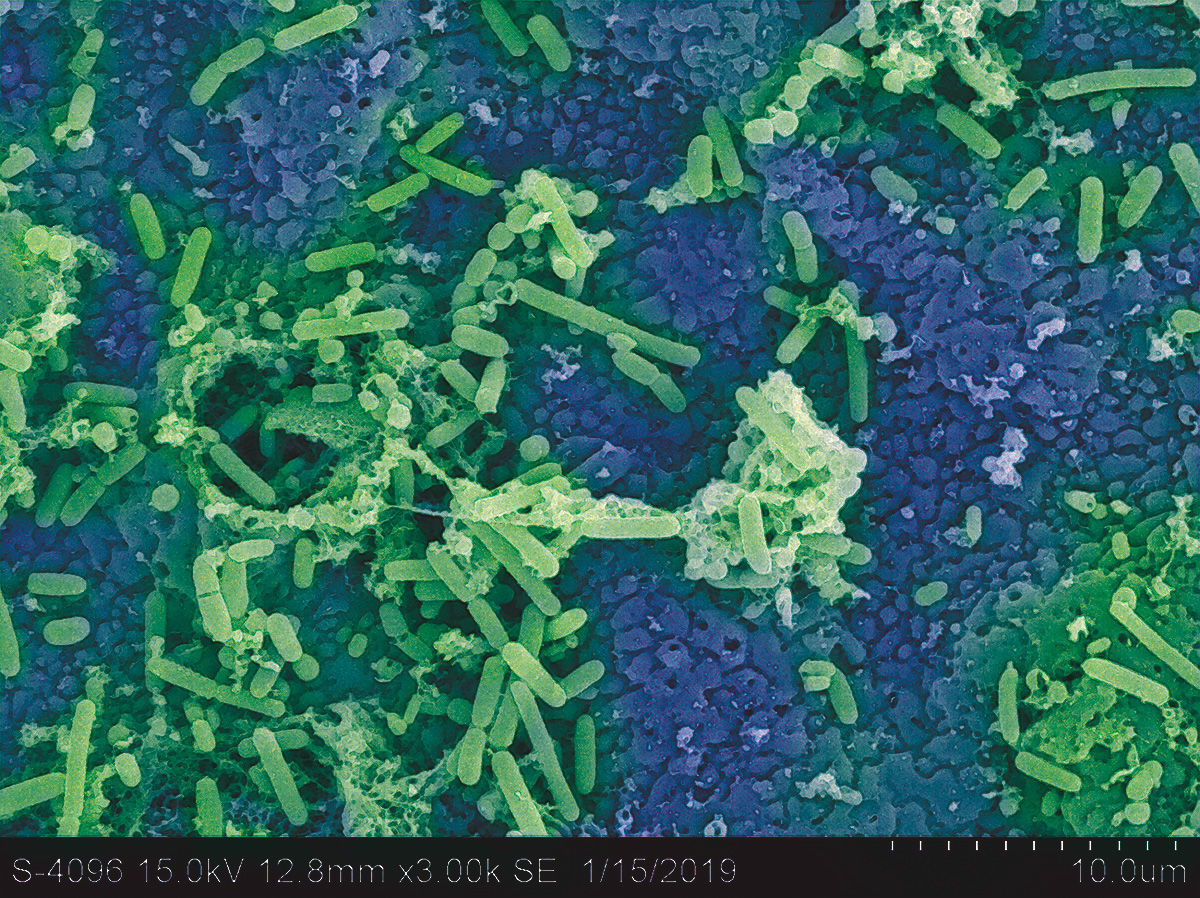

Andoni: We are working on many things. We are working on fermentations. We are working on ingredients. We are working on exploring the technologies we have available to see if we can find new things. And there we go.

Lasa: Apart from the food itself, we are trying to know, in a deeper way, the model for interpretation on the human level. For example, the psychological and anthropological part of our guests. We are working on a very complex model; as you said before, we normally do not know how people will react to this creative experience. While you pay attention to all the parameters you think would be necessary to pay attention to, it doesn’t guarantee success every time because we are a combination of matters, emotions. Maybe that will be our biggest challenge…how to manage the human part of all of these experiences. This is very linked to the rest of the subjects you were talking about. When we are using the word natural in those jams, or the preserves, you are playing with the expectations of the people with the warnings or memories of the color.

Just last year we were working with some psychologists from Germany doing, the name was like, The Meal Experience in Foodness, Gastronomy. We were trying to learn how they react from this creative experience, and we learned a lot. We realized that the biggest part of success lies in the way we [communicate with] them before they come to the restaurant—determining whether they are needle-phobic, or if there is a leader at the table or not. We can be very easily influenced by our surroundings.

Something can happen that can make the experience because we are not making food for pleasure but for emotion. Maybe that is the most challenging part. When you have totally changed your model, it is not a service, but an experience, a business. When you go to a concert or a gallery, why not ask the musician or the painter to change the art because you do not like it. There is no option once you go there; you are in our hands. There are things we can control and things we can’t control. We are going deeper in that sense with trying to understand and know; that is going to take a long time.

This interview has been edited for clarity.