This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 01, Designing for the Human Microbiome. There’s still time to order your limited edition copy here.

Happy accidents have defined the development of the human culinary experience since the early days of our hunting, gathering and cooking. It is for this reason that some of the most mystical and alchemical transformations that take place in our kitchens cannot be traced back to a single discoverer or architect. In this regard, yogurt is one of the most archetypal preparations. While some speculate that it originated in the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia, the birthplace of agricultural civilization now known as modern-day Syria, Iraq, Iran and Turkey, whoever first harnessed the power of this metamorphosis over 7,000 years ago could scarcely have conceived of its subsequent and lasting impact.

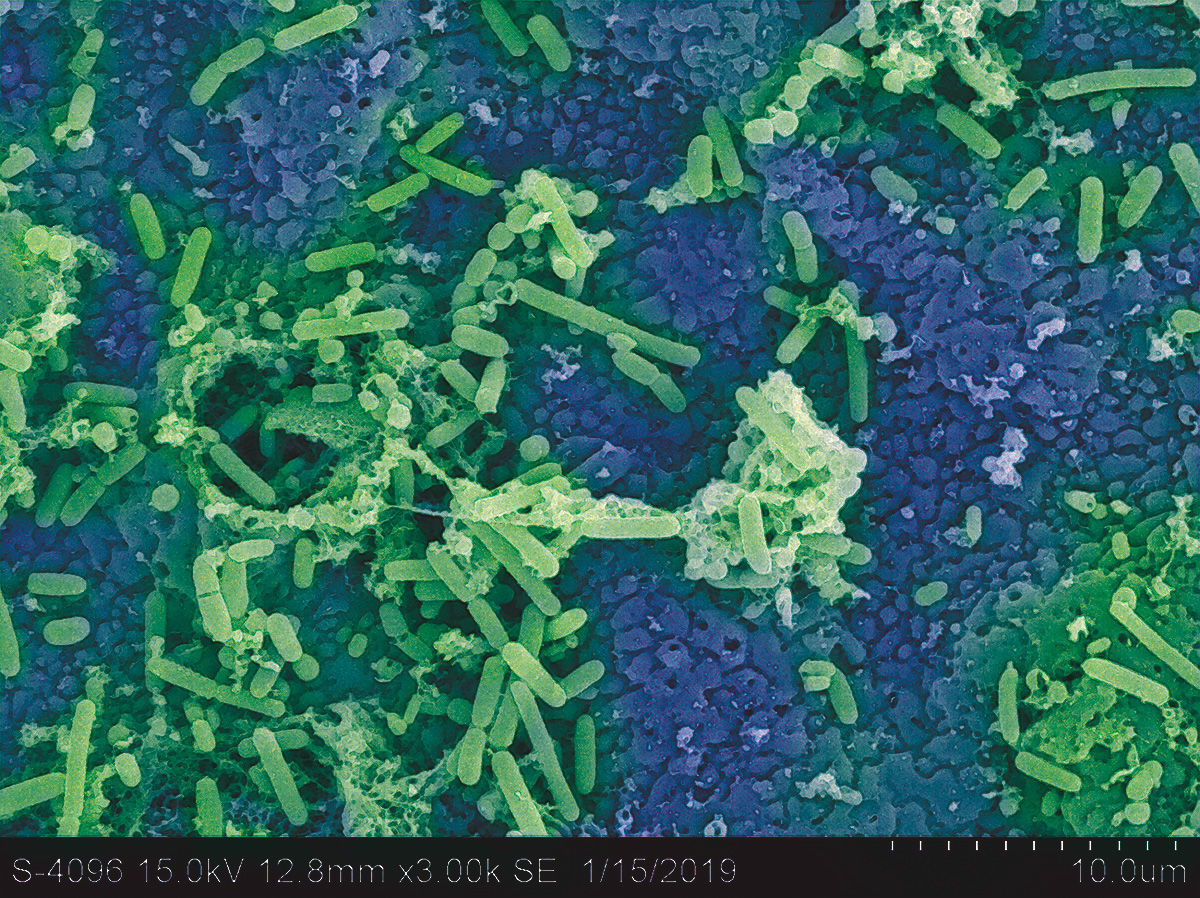

At its core, yogurt, like most ferments, is an innovation that elegantly and deliciously deals with the universal issue of preserving a highly perishable food: this was especially important in the days before refrigeration. It just so happens that the process of fermentation also releases and creates constituents that make milk more digestible, nutritive, health-supporting and scrumptious. The beneficial bacteria that proliferate in the milk consume lactose— the disaccharide milk sugar—and create lactic acid. Moreover, their presence can complement our own gut microflora in their on-going battle against pathogenic and opportunistic microorganisms.

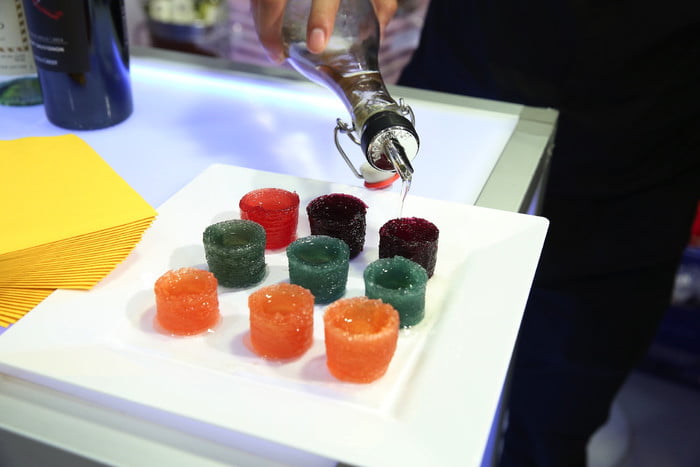

Yogurt making vessels designed by Yiyi Mendoza. Photography by David Brandon Geeting for MOLD Magazine Issue 01.

Yogurt making vessels designed by Yiyi Mendoza. Photography by David Brandon Geeting for MOLD Magazine Issue 01.

The ingredients for yogurt are simple: milk, lactic acid bacteria—namely Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium lactis and other friends—, heat (the milk is taken up to 170–185 ºF for a moment, then held at 95–115 ºF), and time (typically 4 to 24+ hours). Although staying within these parameters will likely yield desirable, edible results, anyone who has tried their hand at making yogurt can tell you that it does not guarantee them. There is as much art involved in the process as there is science. Commercial yogurt producers deal with this by attempting to control every variable to the smallest decimal place possible. Grandmothers and other community yogurt makers, on the other hand, achieve consistency by developing a personal ritual and a deep and innate sense of the process over the course of hundreds of batches. This ritual may involve a special vessel, a hyper-specific zone of incubation, or even a beloved cow whose milk makes better yogurt than that of her sisters.

To say that there are as many ways of making yogurt as there are cultures on this planet would be an understatement; every maker’s touch and technique will differ. What’s more, the diversity of roles that the thermophilic dairy ferment plays in the hearts of homes across the planet and the many ways in which it is integrated into myriad global cuisines is stunning.

However, the significance of this ancient technology is so much more than the sum of all the culinary and health benefits known and yet to be discovered. The most crucial facet of yogurt making, and that which will carry it far into our future, is that it prolongs and deepens the relationship we have with our food. As is the case with all food preparation traditions that take time and the passing on of knowledge, it connects us to our ancestors and allows us to become conduits between them and our descendants. More specifically, fermenting food allows us to engage with a dimension of our world that we cannot see with our bare eyes. It puts at the forefront the chief role of the beneficial microorganisms with which we live in symbiosis. For tens of thousands of years we did not know them but lived in awe of their work, attributing it to the supernatural. Now that we know them and have named them, we can still wonder at just how super and natural their work really is.