This article is part of our “Into Ento” editorial series exploring new territories and ideas around eating insects.

Even before they crept into the United States as the latest freaky food trend, people ate bugs. In fact, 80% of the world already practices entomophagy, the act of eating insects, while the rest of us do so quite inadvertently. According to the reported levels of insect fragments the FDA permits in produce and other food products (like broccoli, canned beets, and chocolate) the average human eats at least one to two pounds of insects each year.

Concerned? You shouldn’t be. In fact, you should probably be eating more.

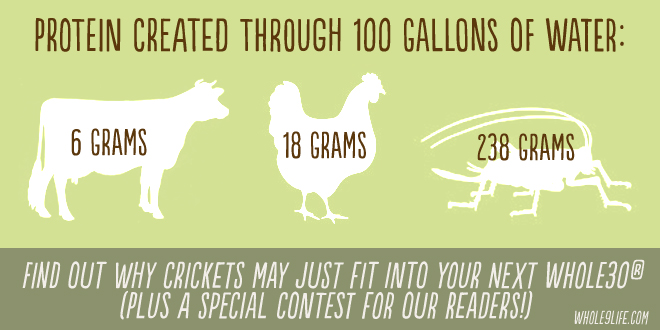

There are over 16,000 species of edible insects globally. They’re abundant, thrive in congested environments, and, unlike traditional agricultural practices, produce minimal amounts of greenhouse emissions. In a world where no less than 805 million people are underfed or malnourished, protein-packed insects have the potential to provide a sustainable means of meeting global nutrition needs.

Health officials, economists, and even the United Nations agree that insects are a welcome addition to the 21st-century diet. It’s now in the hands of food designers to convince consumers to take the first bite.

Crunching Grasshoppers, Crushing Stigma

After serving cricket summer rolls to the crowds during New York Design Week, the MOLD editors witnessed firsthand the Western stigma against eating bugs. Yet less than 0.5% of insects are harmful to people, animals, or crops, and any insects intended for human consumption must pass strict FDA approval. According to entomology professors Marcel Dicke and Arnold Van Huis, insects raised in such hygienic environments are as safe, if not safer, than traditional livestock for human consumption.

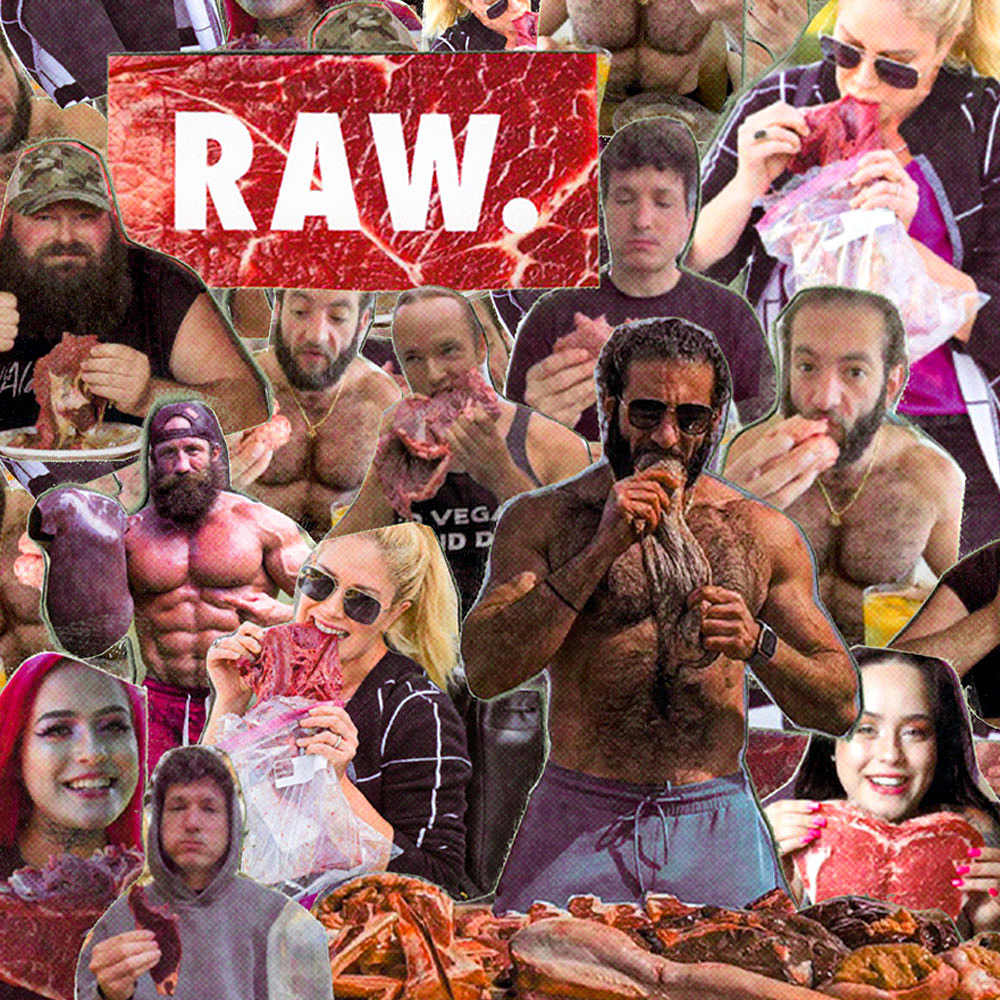

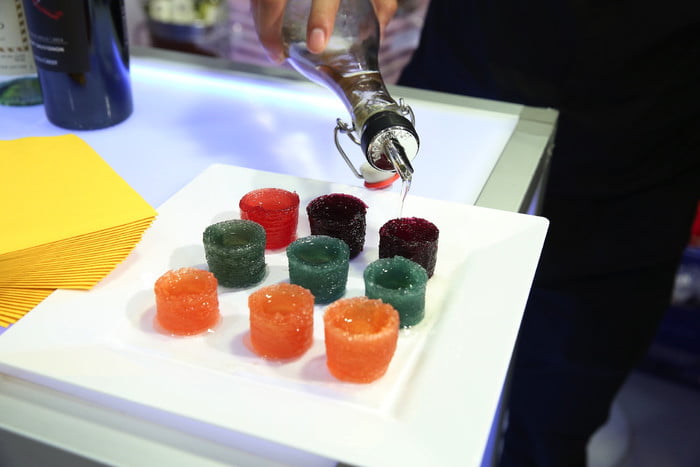

However, entomophagy pioneers aren’t relying on statistics alone to change cultural perception. Some are capitalizing on a powerful culinary weapon: novelty. At a time when restaurant goers are hungrily tucking into offal and pig’s head, chefs are finding diners who are only too willing to shrug off the bug-eating fears held by less adventurous eaters and try something new.

Such is the recipe of success for chef Julian Medina, whose Mexican bistro Toloache serves authentic Oaxacan chapulines topped with grasshoppers (pictured above). Even though grasshoppers sautéed in jalapeños and brushed with a chili-lime seasoning are snacked on like popcorn in Mexico, at Toloache “Customers know chapulines, come in specifically to order them, and sometimes do it as a dare,” explains Temple Kemezis, the restaurant’s event manager, who swears that grasshopper chapulines are “the perfect gateway bug.” Customers who enjoy them, she notes, are much more likely to taste and appreciate other insect dishes, including drinks made with sal de gusano, a salt and agave worm mix.

Healthy Minus the Creepy-Crawly

The novelty factor has its place, but in order for a controversial food to be accepted for everyday eating, it must be designed “beyond the novelty,” insect entrepreneur Matthew Krisiloff tells The New Yorker. “When you think of a chicken you think of a chicken breast, not the eyes, wings, and beak,” he says. “We’re trying to do the same thing with insects.”

The product most likely to change all that is probably Exo, a protein bar made from cricket flour (see first image). The health food startup’s founders Gabi Lewis and Greg Sewitz understand the complexity surrounding consumer eating behaviors. “We aim to change as few behaviors as possible,” Lewis says. “That’s why we didn’t make it into a cricket chip. People get their protein from protein bars. If we change the protein source, we shouldn’t change its format.”

Exo’s strategy to innovate only as much as needed also applies to its flavoring and packaging choices. For mass consumption, the packaging can’t induce an ick factor. That means no imagery of bugs, obviously, but the wording, is important, too. “Exo only uses the word flour,” Lewis stresses. “You’re not going to find legs or antenna in [flour].”

For Exo, Toloache, and a growing community of entomophagists, wider public acceptance is a slow and constant battle. In order to embrace a new protein source, consumers must find it convenient and comfortable, yet exciting and enticing enough to warrant a change in their purchasing behavior. In many aspects, this depends on the ability of designers to create products that place insects in an appetizing light. If they succeed, the world may find a sustainable food alternative. Fail, and that global opportunity might just crawl away.

This article is part of our “Into Ento” editorial series exploring new territories and ideas around eating insects.