This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 03, Waste. Order your limited edition issue here.

To parallel Kevin Costner’s acid flashback induced famous misquote in Field of Dreams1: “If you build it, they will come,” we have to ask ourselves a question that pertains to the boundaries we set for ourselves in the battle against food waste. “If you cook it, will they eat it?”

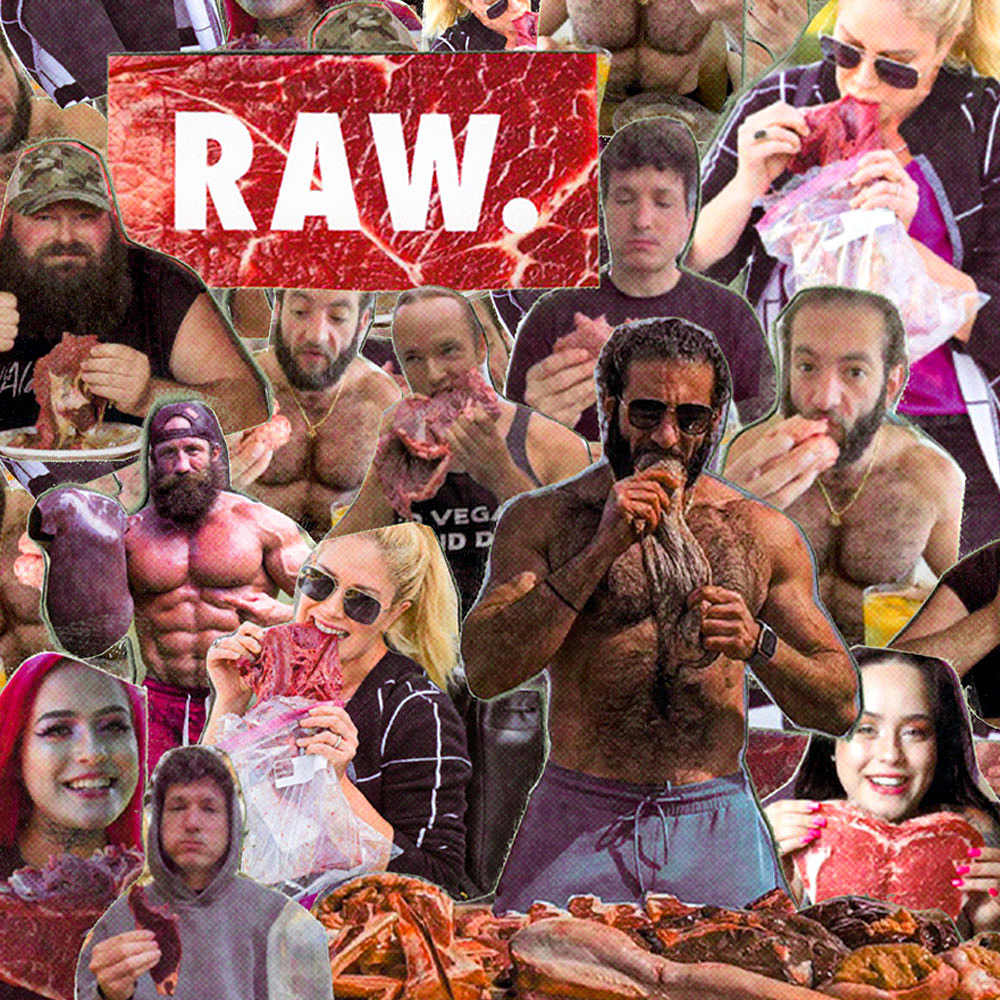

In noma’s fermentation lab, ideation often begins in the garbage bin. Somehow, seeing a mountain of black garlic skins, leftover vegetal pulp from blending flavored oils or scraps of beef from cleaning ribs have of made the R&D chefs at the restaurant cock their heads sideways just a little further. It’s as if only when waste is staring you in the face that your back gets pushed against the wall, and the only way to push back is through creative problem solving. Those scraps all met purposeful and novel afterlives as ‘balsamic’ vinegar, yellow pea jiang, and garum respectively. The upside to such situations is the exhilaration you feel at having championed the ever-present elephant in the room, food waste. The downside is that sometimes you end up creating a new problem for the one you sought to solve.

When I talk about fermentation as a powerful tool, a secret weapon that affords a chef or home cook the ability to divert waste streams and transform every gram of food entering a kitchen into something delicious, I mean it. When you look at waste through microbial colored glasses, that is to say, when you understand the inputs and outputs of fermented food—from shrimp shells and fish guts (which can be autolyzed into delicious fish sauces) to spent grains, or wheat bran (which can be toasted and molded into shoyu)—you stop seeing waste as something useless and beyond hope, and you begin to see ingredients. BUT, there are caveats. Just because you see ingredients all around you, doesn’t mean you have a mouth to put them into. Waste and excess aren’t necessarily the same things.

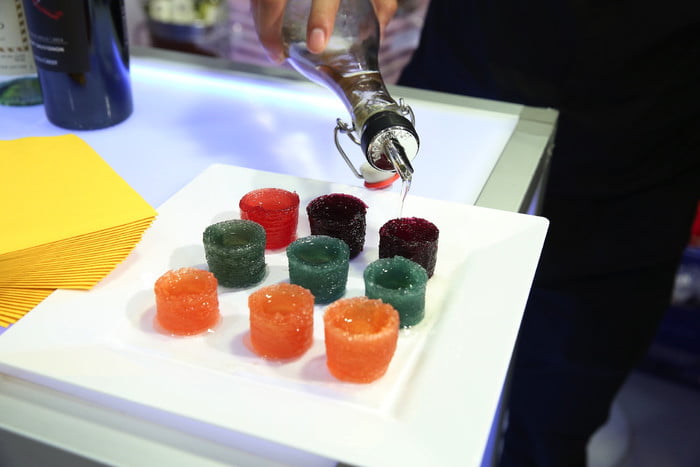

Lacto-fermented cep mushrooms.

Lacto-fermented cep mushrooms.

While you can ferment trimmings, peelings, stalks and stems into delicious foodstuffs as an alternative to throwing them out, the resultant ferments don’t always have the same consumability as the core of the products you stripped them from. While fermentation is a body of knowledge capable of tackling the problem of what to do with food waste, the finished products it produces are often replete with compounds that, while delicious, can out of necessity, only be eaten sparingly.

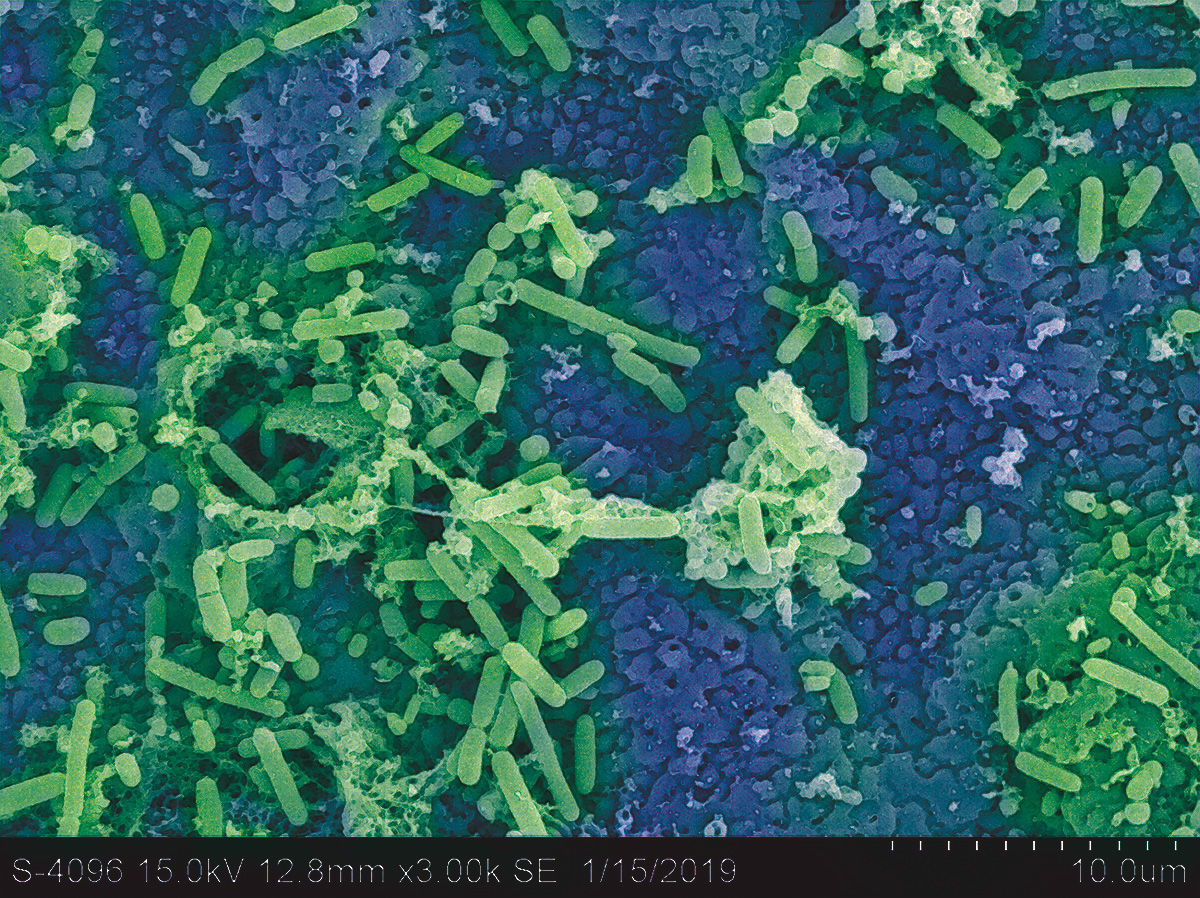

Aspergillus oryzae spreading mycelium on dryad’s saddle mushroom shoyu.

Aspergillus oryzae spreading mycelium on dryad’s saddle mushroom shoyu.

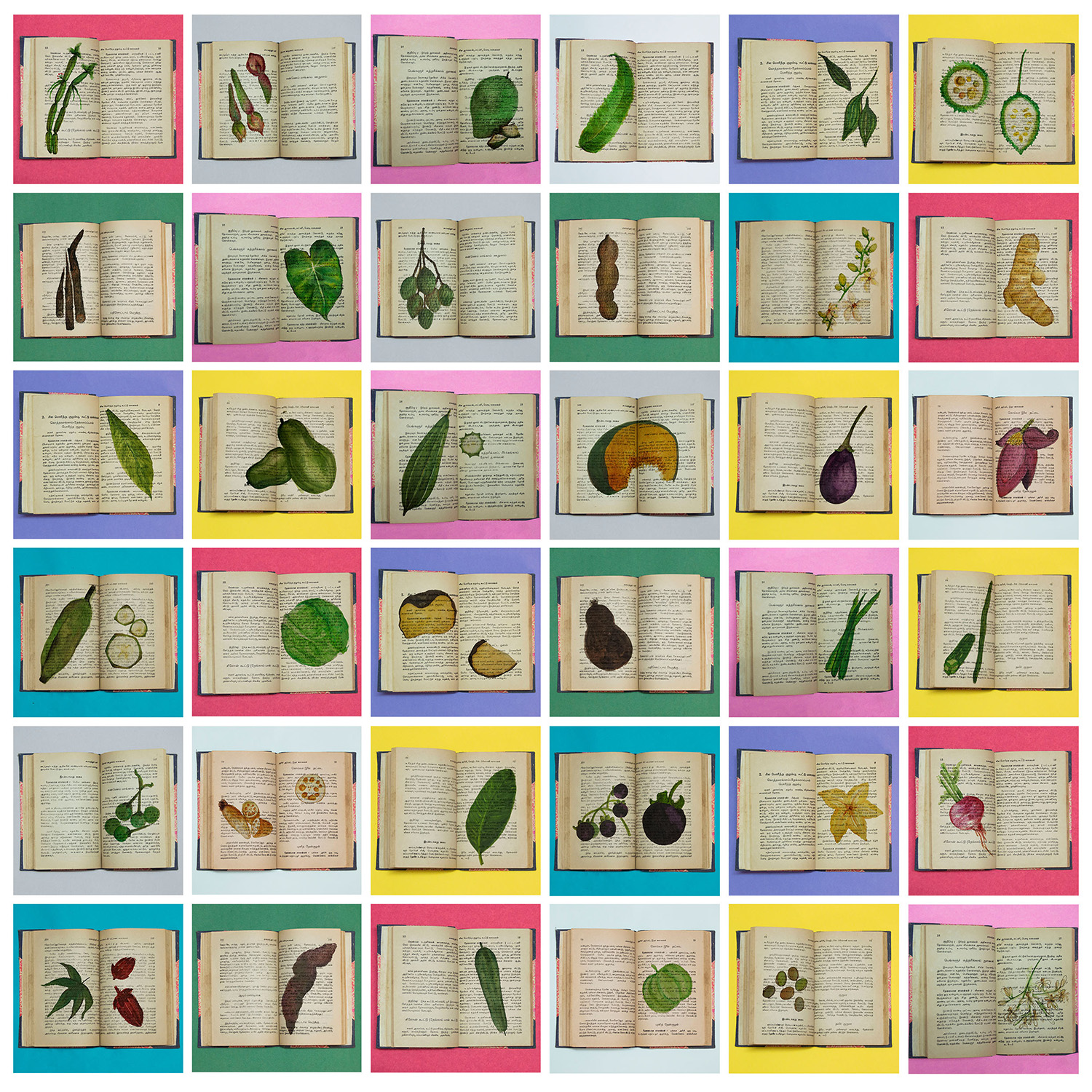

Consider yourself a dutiful vegetarian culinarian? Go ahead and cook a whole roasted head of baby cauliflower for dinner, lovingly basted in butter with sprigs of lemon thyme and pineapple sage. When you’re full, and stare back at your cutting board in the kitchen and see the ribs, leaves and stalk you trimmed off of your cruciferous feast and think to yourself “How best could I ferment those trimmings instead of throwing them out?” Briny lacto-fermentation might spring to mind as a viable alternative. And so, you throw the trimmings into a crock with nothing more than salt, water and whey and let friendly microbes digest and transform your food for you, as you sit, watch and wait. But ask yourself this: Could you ever sit down and enjoy a full plate of sour pickles for dinner? Or sauerkraut? Or miso piled as high as risotto?

Of course not. What fermentation rescues from the bin is often held back from being enjoyed as plainly and thoroughly as the fresh foodstuff it was borne of by your need to preserve it.

High salt or acid contents may keep malevolent microbes out of the picture, degrading vegetables and meats with intended direction in contrast to the chaotic biome of a backyard composter. But by the same token, ferments ingested by humans must be enjoyed in moderation for the very same reasons, lest you end up with a severe case of acid reflux or high blood pressure. This postulation isn’t intended to dissuade creativity, nor the goodwill required to believe that there must be another way. Understanding the limitations of solutions is sometimes the best way to push creativity even further, in lieu of settling for an imperfect panacea.

At noma, when we harvest mounds of wild rosehip petals at the height of the summer to blend into the most fragrant and potent rose oil you could imagine, we’re left with equivalent mounds of rose pulp once the plant matter is separated from the flavoured oil. We divert the stream of waste by folding it into miso, blending it into garums, or brewing it into kombucha, giving it a second life in each instance. But even for a restaurant as busy as noma, we’ll run out of the intended ingredient (the rose oil) long before we’ve cooked our way through the miso or garum. But it’s only to the credit of the first outlet we conceived of for channeling waste into a useful and delicious medium that we now have the whole flight of floral potions to pepper our menus with.

While we may wish we could use every other application of rose pulp at a 1:1 pace with the oil that makes its way into vinaigrettes and onto langoustines, it just isn’t possible. Which means that at times, we have a lot of these ferments around. It’s by no means a bad thing, as once these products are shelf stable, they can simply sit and improve. But still we’re left to wonder if there isn’t still an even better way. Could industries not cross pollinate? With the waste product of one being fed to the consumers of another? (last year I came across an anecdote about a huge coffee company that would sell its used grounds to a perfume factory, so they could extract any remaining aromas). The quest of the maximization of profits in big industry all too often leads to egregious waste. But by dedicating time to the creation of value, waste can just as easily be another opportunity to profit.

Aspergillus oryzae sporulating on dryad’s saddle mushroom soyu.

Aspergillus oryzae sporulating on dryad’s saddle mushroom soyu.

.

Humans are adaptable, we’re problem solvers by nature. Even (or especially) when the problems are of our own creation, the challenge of facing the possible spurs us on. We employ the best tools at our disposal (be they technological, or biological) to dig ourselves out. At noma, we think of fermentation as advantageous a tool as the stoves, or our knives. Ultimately, changing perceptions around what can and should be eaten will be paramount in the battle against waste, but until then; sour, rot, age, bubble, and brew your way to a greener and more delicious world.

1: The actual, less impactful quote was “If you build it, he will come.” Chalk this one up as a case of collective, selective amnesia.

The Noma Guide to Fermentation, David Zilber and Rene Redzepi’s new tome to fermentation, is out today on Artisan Books. The chefs will be touring the US and Canada in support of the book. See noma.dk for more dates and information.