How to read a recipe? How to write one, in Tamilakam?

The ancients said that there were three grand academies, or Sangams/Cankams, millennia ago in what is now Tamil Nadu state in southern India. These academies created a canon of works that came to be known as Sangam literature. The dating of this supposed golden age of culture is still disputed, but estimated to have been sometime between 300 BCE and 300 CE. The first Sangam is believed to have been on a piece of land below Kanyakumari, the southernmost tip of India, the end of land today. Both the first and the second Sangams are said to have been submerged, their entire works lost to sea. While the myth-making takes predictably exaggerated forms in these times of parochialism, that there is a possibility of a natural disaster, perhaps a tsunami, that might have taken back land and its people cannot be dismissed, say scholars of the tradition.

What fascinates me is that nascent research about this period shows that during the Sangam period, a popular dish was pomegranate arils fried in butter, with fragrant curry leaves. Although autumn nearly here, the story of Persephone is my favorite myth. In one version of the story, Persephone is abducted by Hades, the god of the underworld. Her mother Demeter, the goddess of grain, crop and harvest, is furious, and mourns her missing daughter by plunging the Earth into a deep winter where the crops wither and die. The equally devastated Persephone refuses to eat or drink in the Underworld, also because that would bind her to Hades forever. Finally, Demeter manages to find her daughter, who, just before she comes back up to Earth, eats six arils of a ripe red pomegranate. She is thus bound to spend six months of a year with Hades as the goddess of the netherworld. During those months, Demeter mourns by giving the Earth its autumn and winter seasons, until Persephone returns and we have the warmth of spring and summer again.

How could a story that fierce not stay on in the mind? What must the arils in butter with curry leaves taste like? Where was the recipe set in Tamil country?

The place is important because in Sangam poetry, the poems couldn’t swerve from tradition. Tradition insisted that the poems, most of them emotional verses of love, longing or bereavement, written during the third Sangam and the only ones which have survived, follow strict rules. These rules were incredibly complex.

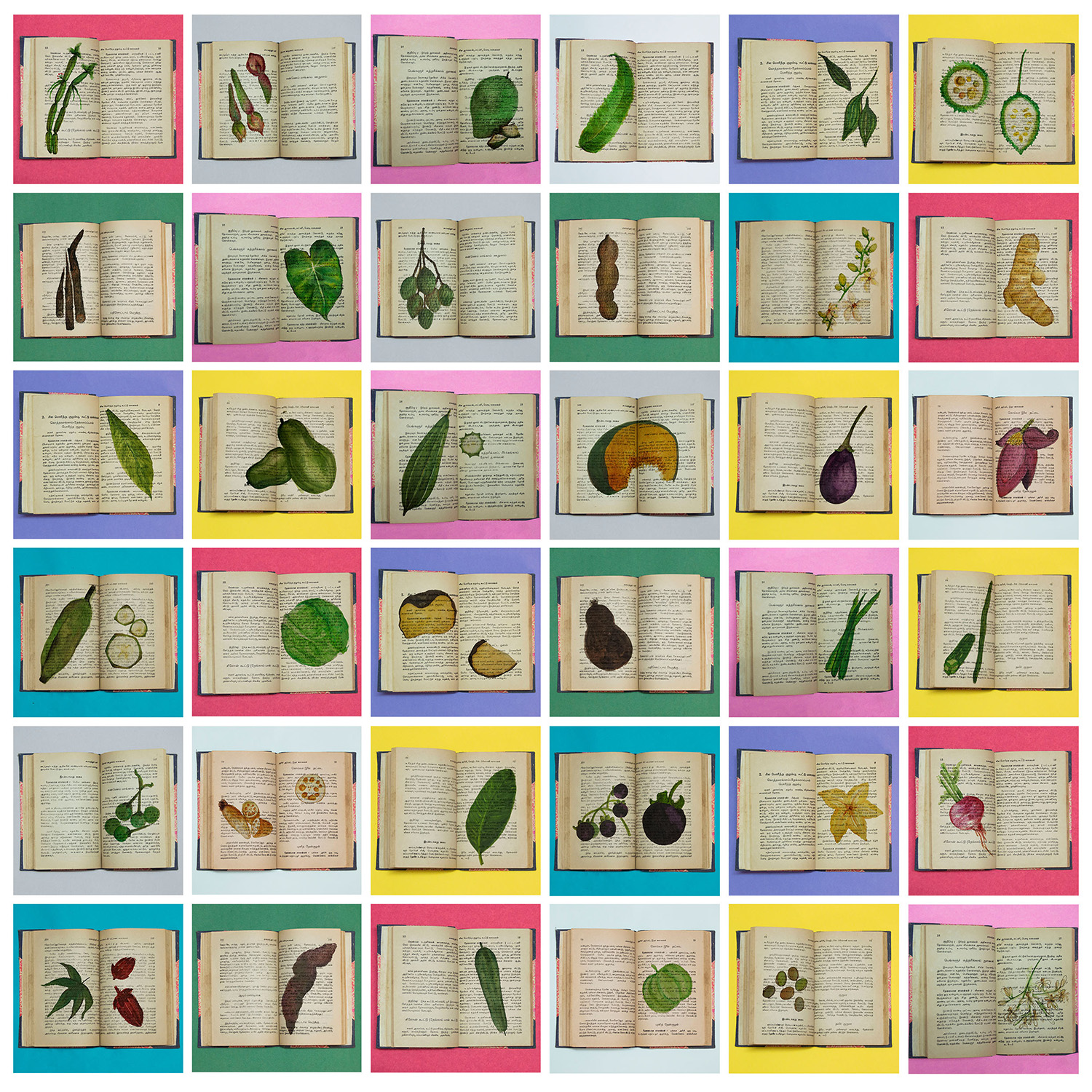

Firstly, the region that today includes nearly all of Southern India, then the Tamil country, was divided into five thinais or geographical features. Kurinji was mountain region, Mullai was forest, Marutam, cropland, Neital, seashore and Palai, desert or dry land. Further, each of these thinais were assigned specific feelings: union (of lovers), waiting, quarreling, pining and separation respectively. A wide range of specific themes that would suit each landscape were further derived. Each thinai had a flower, a particular time of the day, a season, an animal, a crop, profession and even a particular god attached to them. Thus, for instance, a poem about a lover’s quarrel might be set in the paddy fields, at midnight, in the cool winter months. The protagonists and the actors on the side-lines were never named. They were always a he, a she, a they, her mother, his father, her friend, and so on.

The Gangaikonda Cholapuram temple in Tamil Nadu was constructed during the Sangam period.

The Gangaikonda Cholapuram temple in Tamil Nadu was constructed during the Sangam period.

Despite these clauses, Sangam poetry remains a bottomless resource to understand the culture of an ancient people. Within these poems were included every aspect of life. Between lovers, in the courts of kings and on the streets, food was important. It was enjoyed, celebrated, and was in the background of every other cultural event, just like today.

What I imagine survive are ideas of dishes that were once commonplace but now seem unlikely. Recipes, like those my mother lends me, are never wholly written down. There is a lot of eyeballing—that is how I learnt to cook. In the Sangam centuries, meat was predominant, again discounting the narrative that ancient people had plant-based diets and hence, were that much more pious and pure. It is a narrative that a new order of people in power who want to prescribe eating habits and thus decide who is a real Hindu or not, thrust upon Indians, erasing histories, facts and cultures of many communities. Post-truth.

Research of Sangam poetry shows that iguana and rat meat was popular. Without tomatoes, garlic and onion, what flavored food were coconut, coriander seeds, tamarind and pepper. While tomatoes are now an essential in Indian cuisine, it was only the 16th century onward that they began to be used after the Portuguese introduced them in the subcontinent. There are conflicting schools of thought over where and when onions and garlic originated, but researches of Sangam era food believe that these people did not use either. Well before the omnipresence of Persian-influenced biriyani rice, there was the practice of cooking vegetables and meat together in rice.

The pomegranates were a regular supplement, it is said. I wish the recipe was fully written, because just butter and curry leaves seem incomplete. Wouldn’t the fiery red of the arils melt away in butter, I wonder.

If the recipe only contains the kernels of the final dish, how does one look back into a language that carries so much historic memory and cook a dish? The Sangam period and the astounding literature it produced is still a partly-solved mystery. New readings bring new understandings of an evolved culture from once upon a time, long, long ago. When the poems have lived, why have favorite recipes been erased from daily use? What do we choose to remember? Why do we relegate what we relegate for erasure?

This story is part of a monthly series of writings from writer and artist Deepa Bhasthi on the intersection of language, landscape and food.