In a Trump-era America, where our food safety acts are under attack and when access to food education is more contentious than ever, being a stay-at-home mom has become particularly politicized. Issues ranging from equal pay to women’s reproductive health have become lightning rods and effect everyone from Melania to Betty Crocker. While the production of food may not necessarily be gendered, the performance of interacting with food in private spaces has been historically carried out by women as caretakers, slaves and domestic workers.

LAZY MOM is an art duo started by Phyllis Ma, a window dresser, and Josie Keefe, a prop stylist. Based out of New York City, Ma and Keefe take on the identity of a messy house wife with a penchant for sexual innuendo and Willy Wonka-esque aesthetics. While they both attended Columbia University, they actually didn’t meet until they both joined an online art collective called Family Family Tree, allowing them to fuse their interests for a trial zine called LAZYWOW, which focused more on simple aesthetic food still-lifes, not yet filled with the same political and humorous undertones as their work now evokes. Since the explosion of their images online, they’ve worked with varied clients, from The Standard Hotel’s restaurant Narcissa to creating a feature for Lucky Peach’s “Obsession” issue. In contemporary art contexts they’ve displayed their work everywhere from the object-based Fisher Parrish Gallery (Co-founder Zoe Alexander Fisher has been a longtime champion of their work) to Printed Matter, and, a booth at the art fair NADA in which they created work that could literally decay before attendees eyes.

Since our first interview with LAZY MOM, their work has surely evolved. They’ve even filmed a video with Bread Face Blog—a natural collaboration given that the LAZY MOM character the duo evokes, is disembodied in the same way that Bread Face Blog’s (an Instagram sensation inspired by a genre of film that makes women eating into a sexual feat) driving character has always been left mysterious for viewers.

A new wave can be felt in LAZY MOM’s work, she’s revved up and more political than ever, lacing up her apron in a new body of work to “Eat the Patriarchy.” Here, we talk to the duo about what it means to be working with food art in our current political landscape, and new things LAZY MOM has got cookin’ up.

How has Trump’s America affected the work you are creating?

Josie Keefe: Our original idea behind the character of LAZY MOM is that she is a woman fundamentally unfulfilled by contemporary motherhood. Conventional wisdom says that motherhood is the most rewarding thing a woman can do with her life, but to us, MOM is always looking for more. However, she doesn’t care to seek satisfaction in the corporate workplace or through a career. Instead her path to fulfillment is through creative absurdity. She knows she should make her kids’ lunch, but simply can’t bring herself to do it. Instead she stacks food ingredients, creating and destroying elaborate and confusing structures simply because it’s better than the alternative. If motherhood is in essence a job that maintains survival—a mother’s first and primary job is to feed her child—than lazy motherhood is a rejection of survival in favor of the unessential. Nothing LAZY MOM makes benefits anyone, no one is nourished by it, it is useless, wasteful, and absurd.

Phyllis Ma: Right, you can also say that it’s beneficial first and foremost for MOM, because she has taken the role expected of her, and reversed it in a way so that she’s the one in control. She’s cooking and preparing food the way she wants. In that sense, LAZY MOM is feminist project moonlighting as food photography.

JK: At its core, LAZY MOM is about the social expectation that women should feed and nurture their families and loved ones. This idea has been deeply ingrained into human society for centuries.

PM: Post-election, it felt like there was a dank cloud hanging over everything. It definitely pushed us in a different direction. It didn’t feel right to just keep making funny or pretty things, but at the same time, we needed a humorous and absurd outlet more than ever.

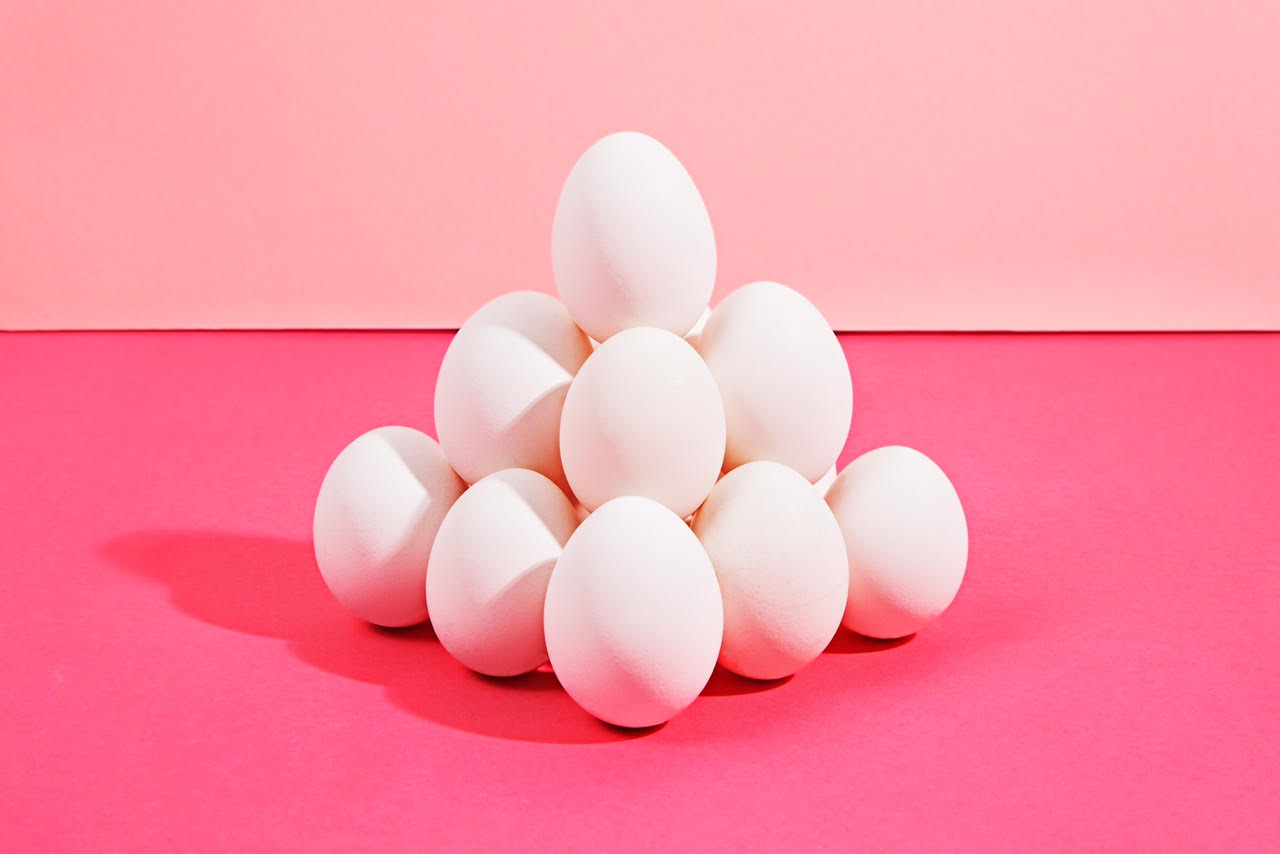

We came up with a project called “Eat the Patriarchy,” a series of photos and videos that showed castrated hot dogs and smashed eggs. It’s a lot simpler than our other photos because we wanted the political message to be clear. We turned it into a postcard set and donated all the proceeds to the women’s shelters at the Henry Street Settlement in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It felt like a productive way to vent our anger.

Is the produce you use from cheap supermarkets or is it important to incorporate organicism? Are these pragmatic choices (ie: what’s cheapest/ readily available), or are the ingredients, beyond their aesthetic value, also important to consider?

JK: We always use the cheapest products and produce we can. In a perfect world we’d love to support organic agriculture, in our practice and daily diet, but we are literally starving artists. Also, our work is very much about the standard contemporary American diet, not the idealized one. The food we shoot is mass produced, usually from large corporate food brands, full of dyes and preservatives. The way our culture eats is really fascinating, Americans in general have become completely anesthetized from what they eat. We are literally eating ourselves sick.

PM: Processed foods are so interesting to shoot–the shapes and colors have evolved far beyond nutritional value. For me personally, it also comes from a sense of nostalgia. I ate a lot of processed and microwaveable foods growing up because my mom was too busy to cook. Especially hot dogs, Wonder Bread and American cheese–now all classic props for LAZY MOM photos.

JK: I was never allowed to have any processed foods as a kid. My parents were deep into macrobiotic cooking and health foods before they were mainstream. Of course, I lusted after sweets and deeply processed foods and all I wanted was junk food.

PM: When we do incorporate organic foods, it’s ironically not to highlight organicism. For instance, one time we needed tomatoes for a taco shoot, but the generic brand literally looked like desaturated blobs. So we just had to buy the fancy kind.

Your work, particularly of late, seems to take interest in the abject. What does it mean for the housewife, the anchor of the nuclear home, to be messy, make typically inedible combinations and use materials that can often leave stains?

PM: We enjoy being messy. When it comes to food photography, the goal has always been to make everything look immaculate, and we’ve always pushed against that. It confuses people. They see a colorful photo of food and immediately they associate it with an ad or a cookbook. It also lends humor and absurdity to our LAZY MOM character–that she doesn’t really care to be perfect.

JK: It is really fun to destroy things-MOM is a pyrotechnic, she loves squishing food with her bare hands, she loves smashing things. Even when we try to do a more conventional shoot, often times at the end, we wind up taking the objects to their messiest, most destructive extreme. The work we make is a cathartic experience for the character LAZY MOM to express her frustrations with social expectations in an physical and creative way.

Processed food, microwaved dinners, all worked to make the housewife’s life more efficient. But what does it mean for you to use/portray processed food, particularly given the fact that these industrialized practices actually have the potential to pollute our bodies?

JK: Mass produced food was originally sold as a product for female liberation. Ironically, through mass produced food, both men and women have become fundamentally alienated from what they eat day to day, to the point where a large part of the conventional American diet isn’t really ‘food’ anymore.

PM: Yeah, so many chemicals and preservatives. Since processed food has so little nutritional value, it’s very fitting that we are photographing it not as food stylists, but as artists. We’re not trying to make processed food look delicious. We’re okay with it appearing inedible or even disgusting.

Also, how do you feel about creations such as Soylent in relation to this?

JK: Soylent is just a techbro repackaging of Slimfast and diet drinks that women have used for decades. The only innovation is nerd-masculinizing a meal replacement drink, with good graphic design. That’s all I have to say about that product.

PM: I tried Soylent once and it tasted awful! Which makes it extra depressing that it was invented so people can work longer without leaving their computers. I’m really against it as a meal replacement. Unless you’re performing open heart surgery or other life-or-death kind of work, you really should get up and go get food. It’s just a practical signal that you’re human and you need a break. I have a feeling that Soylent is another one of those instances where man tries hard to outsmart nature and fails. How our bodies interact with the chemical bonds in food still isn’t understood entirely. The same thing happened with the vitamins and supplements craze in the ‘70s. And now there are so many studies showing that vitamins can lead to higher chances of getting cancer.

In a way you’re able to hide behind this identity—we never see or hear, this LAZY MOM. Her hands, disembodied, focus more on what she’s creating than her personality or physical attributes. Was this your intention? If so, why is this important?

PM: The mysteriousness is definitely intentional. The focus on food gives us a creative constraint that allows the viewer to fill in the blanks. And in another sense, we can be chameleons and make work that’s either very political or very abstract. We never really spell out the backstory of LAZY MOM explicitly because it’s not necessary.

JK: I personally am pretty shy, so it’s nice to have a facade to hide behind. Plus everyone is too obsessed with themselves these days anyways, it’s nice to have an art project that doesn’t focus on images of the artist. Even though there are photos of us out there, people have wild imaginations about who LAZY MOM is—most people are pretty surprised to meet two young, childless women.

PM: Yeah, I kind of like it when people assumed we’re a housewife in the Midwest.

What excites you about the future of food? How do you see your work evolving? Any upcoming projects?

PM: I hope that people will consider the future of food not in isolation, but very much connected to other issues like climate change, agriculture, labor rights and human rights.

JK: I’m excited for food chains to become less wasteful. I love the ugly vegetable project, which brings awareness to how much produce (25%) is wasted simply for being unattractive, abnormal or asymmetrical. France recently made it a law that all supermarkets must donate their surplus food to the needy instead of throwing it away. RFID chips and ‘smart’ supply chains also have huge potential to make the food chain more efficient. The world produces more than enough food to make sure everyone is full, it’s just a matter of distribution.

PM: Right now, we’re shooting an ongoing monthly food column for NEON, a German magazine. The column is a playful inquisition into whether complicated recipes are really worth it–a common dilemma for us millennials. Down the road, we’d like to make longer animations and do more music videos. If there are any bands out there reading this, please hit us up!