Read this story in Japanese here!

In the hierarchy of ingredients, grains often get the short shrift although they occupy the foundation of our food pyramid and our food system. Chefs like Dan Barber and Enrique Olvera have publicly lamented the quality of wheat and corn, respectively, and beyond brown or white, most people wouldn’t be able to differentiate rice quality. Momoko Nakamura is on a quest to change that. The Tokyoite launched Kiki Musubi, a hand-selected seasonal rice delivery service at the end of 2017 with an eye towards education and a focus on deliciousness.

When mutual friends introduced us, it was an instant kinship with Nakamura. A passionate storyteller, Nakamura is a polymath in the food world earning her chops producing food content for brands like Iron Chef, MasterChef and the Food Network while training in traditional Japanese eating practices and macrobiotics. But as she became more involved with local Japanese producers and entrepreneurs, she realized that her personal dedication to traditional food ways and high quality ingredients could have a larger impact. Kiki Musubi and Nakamura’s consultancy, The Momo Co., have become a vehicle for connecting Japanese agricultural producers and their products with the rest of the world. Through the Kiki Musubi rice subscription service and highly curated event programming that includes a private dinner series and countryside retreats, Nakamura is changing the way we think about rice, one grain at a time.

We spoke to Nakamura, aka The Rice Girl, about becoming a rice meister, the concept of 24 seasons, and the daunting challenge of educating consumers.

MOLD: Are there other rice sommeliers in Japan?

Momoko Nakamura: I’ve decided that “sommelier” isn’t the appropriate term for me. I am simply hugely enthusiastic about and charmed by rice! Hence my alias Rice Girl. I eat rice, I talk about rice, I dream about rice, and I think about rice. Every single day. And in fact, for as long as I remember. My earliest childhood memories revolve around rice, and I’ve always insisted that my most ideal last supper would be a simple bowl of rice. To me, being discerning about the rice falls under the same category as having preferences around water. It’s everyday. For the bourgeoisie and proletariat alike. Rice Girl serves everyone. “Sommelier” somehow didn’t to fit that sentiment.

There are rice industry professionals throughout Japan—from the farmers who grow the rice, to those who wholesale rice, to the rice specialty shop owners who still maintain their city shops from yesteryear, and the department store buyers. There are associations that offer courses to obtain certificates as a “rice meister” or a “rice sommelier”. Getting certified for niche areas of interest is hugely popular in Japan.

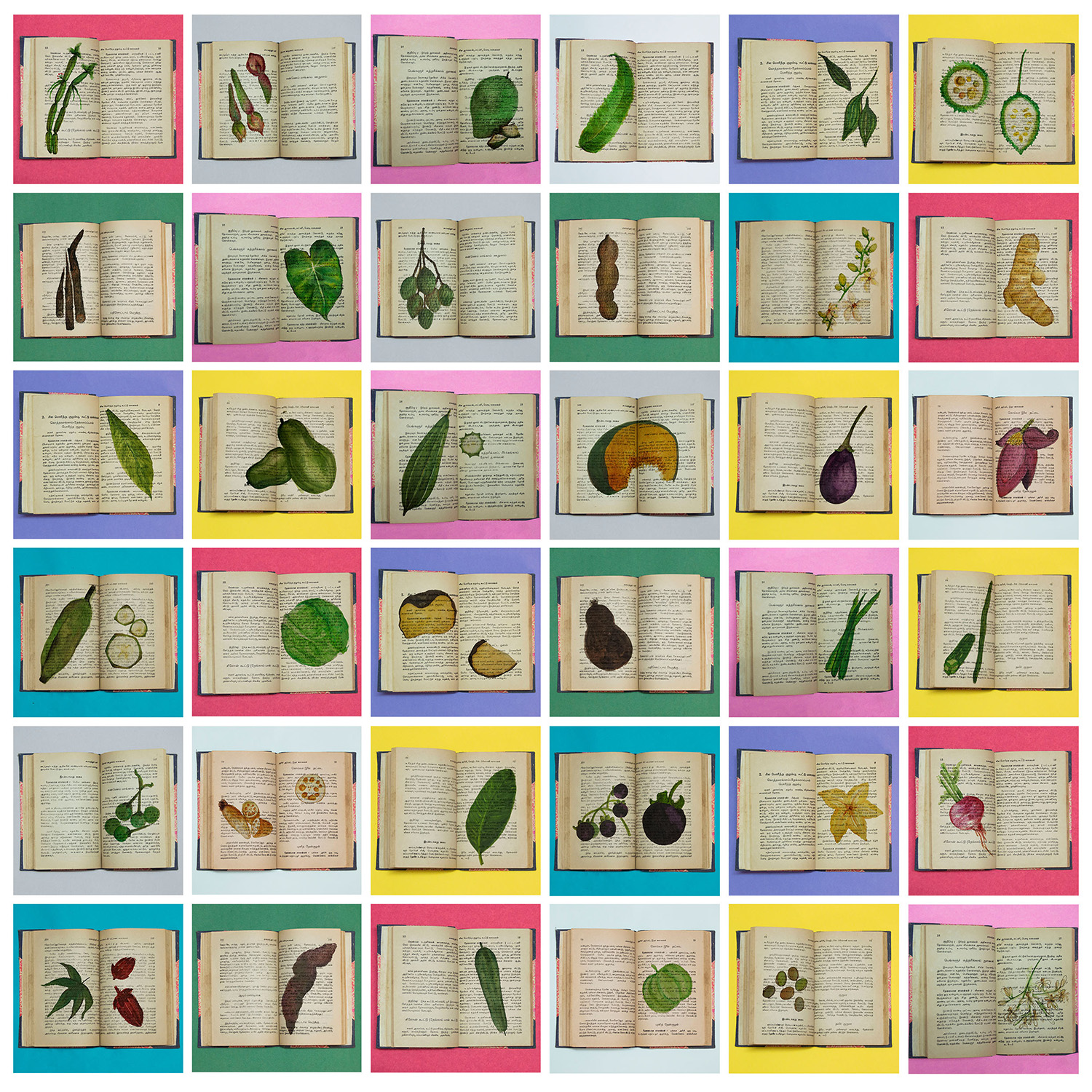

Nuka-zuke pickles made by fermenting vegetables overnight in a bed made with rice bran, the part that’s removed when polishing brown rice into white rice.

Nuka-zuke pickles made by fermenting vegetables overnight in a bed made with rice bran, the part that’s removed when polishing brown rice into white rice.

Where did the idea for a rice delivery originate from? Are there other similar services available in Japan?

Japan Centre in London seems to offer a subscription-based rice delivery service. From what I understand, it’s rice that’s selected from their current roster of big brand products. And there are certainly of-the-month clubs for every food and non-food product imaginable, in every corner of the world. In Japan, there are plenty of CSAs or farm box deliveries that include rice. Rice can be purchased online from many stockists, and naturally, most retailers deliver your groceries, and that often includes rice.

But this abundant access to rice hasn’t made the average person very discerning. Or perhaps the abundant access to rice has been the root cause all along.

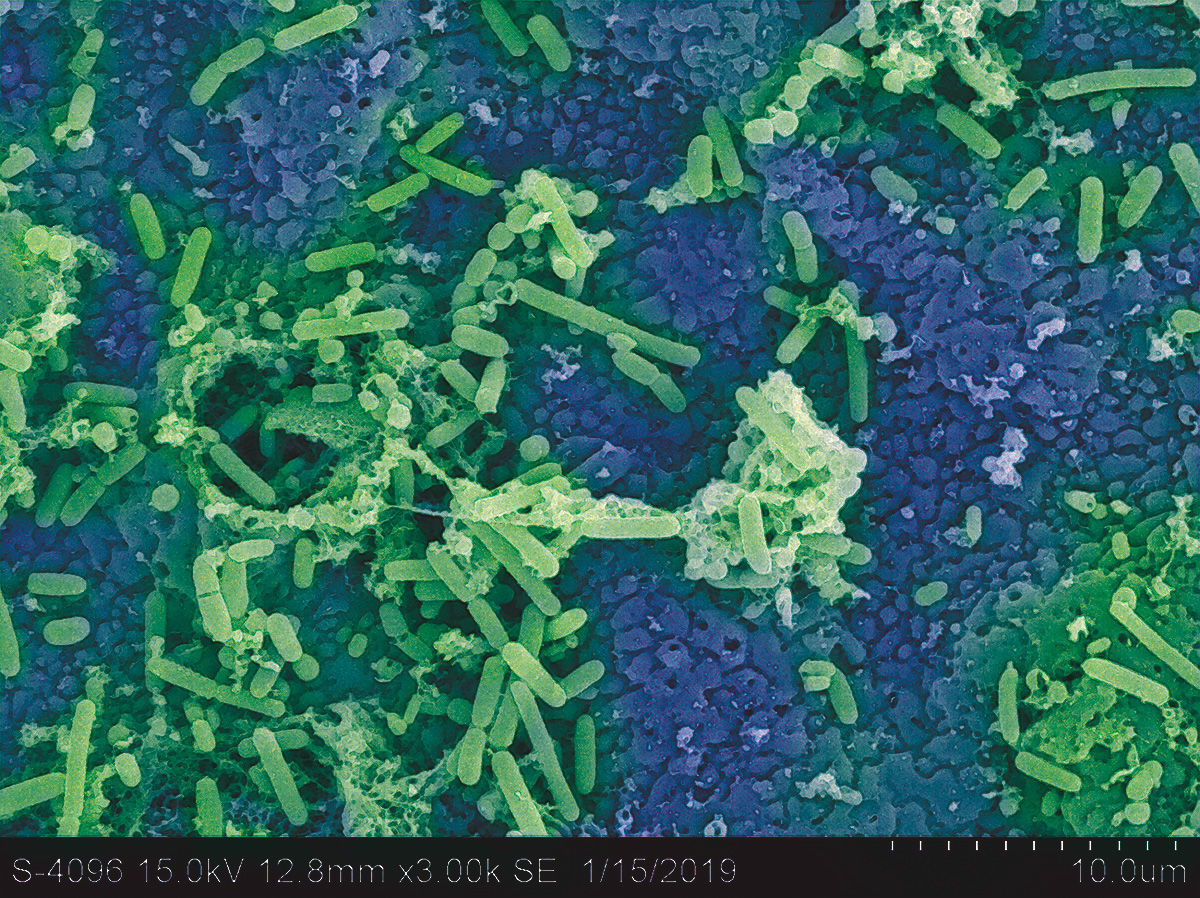

Rice, as with any large scale farming, has historically been laced with an alarming amount of fertilizers and pesticides, and handled not as food but as a commodity. And as such, the grain we get at home is equally natural and chemical. During WWII, parts of Japan were dealing with hunger. No longer indeed. Thanks to man-made chemicals and technology, we have rice, and a lot of it.

Good rice in Japan is a given. But that doesn’t mean that the world, let alone Japanese people, are aware of the diverse portfolio of Japanese rice. It’s not sexy. Yet.

Through my previous work in food media, I was living in a world where if my product didn’t reach tens of millions of people, then there was no value. As Rice Girl, my interest is in connecting passionate rice farmers who tend to their rice using traditional Japanese natural farming practices, with those who fully appreciate the love and care that this kind of farming requires. The work put in results in superior rice. Each varietal showcasing unique notes, textures, and uses. A true testament to quality over quantity.

As a food industry consultant, have you seen a renewed interest and care in rice quality/varieties in Japan?

There is absolutely a renewed interest in rice. In interest in where all of our food comes from, really. We are a generation raised on microwaves and washing machines and rice cookers. We are children of “faster,” “cheaper,” “more”. I used to be quite judgmental about all of that. But I realize that that innovation was a product of immense hardship that preceded it. And I am in this place of incredible luxury as a result. That said, it seems that we in Japan, as well as many other parts of the world, have realized that the pendulum may have swung a little bit too far. And we are finally beginning to u-turn. We recognize that the handiwork and craftsmanship of our grandparents’ generation has a human-ness that we crave. My attention to a single grain of rice is an ode to that.

We notice that your focus is on 24 seasons—can you explain this concept? We thought there was only 4 seasons!

We all know Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter. It’s the commonly accepted categorization of seasons. Yet somewhere in the back of our minds, we simultaneously understand that after three months of Spring, it is not suddenly Summer. Do we not? It is a gradual change that happens day to day to day. The traditional Japanese seasonal calendar takes these four major seasons and breaks them down into 24 sub-seasons, which then breaks down into a total of 72 micro-seasons. Essentially acknowledging the changing seasons every five days.

This is a concept that, like much of Japanese culture, was borrowed from ancient China a couple of thousand years ago. It has since pivoted and edited to reflect Japanese climate, culture, flora and fauna. The calendar reads as poetry—telling the story of a full year. As you can imagine, farmers, saké brewers, ceramists, florists and cooks—all artisans—who work closely with the land listen to this story.

For the purpose of Kiki Musubi, I focus on the 24 sub-seasons.

Kiki Musubi Delivery #008: WINTER SOLSTICE BLEND. 22 December 〜 4 January. The Winter Solstice is when the power of the sun is felt most dimly here on earth. Japanese eat foods that end with the last letter of the alphabet during this time, marking an end and giving a nod to a new beginning: kabocha, udon, lotus root, carrots, kumquats. In China, the Winter Solstice is also referred to as the Sun Returns. Moose shed their horns, and prunella and wheat begin to bud amongst the weight of the snow. While these days are quieter, there is movement in the universe and the dawn of the next can be anticipated. In Japan, yuzu are dropped into the bath the evening of the Winter Solstice – keeping colds away and rejuvenating the body and soul in preparation for a fresh start.

Kiki Musubi Delivery #008: WINTER SOLSTICE BLEND. 22 December 〜 4 January. The Winter Solstice is when the power of the sun is felt most dimly here on earth. Japanese eat foods that end with the last letter of the alphabet during this time, marking an end and giving a nod to a new beginning: kabocha, udon, lotus root, carrots, kumquats. In China, the Winter Solstice is also referred to as the Sun Returns. Moose shed their horns, and prunella and wheat begin to bud amongst the weight of the snow. While these days are quieter, there is movement in the universe and the dawn of the next can be anticipated. In Japan, yuzu are dropped into the bath the evening of the Winter Solstice – keeping colds away and rejuvenating the body and soul in preparation for a fresh start.

How do you source your rice?

I rove the Japanese countryside and meet directly with rice farmers who grow rice using traditional Japanese natural farming practices. They do not abide by any standardized farming methods, but rather consult with the soil, water, climate, environment, and leverage the natural surroundings to tend to their rice. Needless to say they farm using absolutely no fertilizers or pesticides. It’s a constant loving dialogue with nature. And perhaps because of the care this type of farming requires, most of these farmers are kooky and wonderful and charming and are literally making the earth a better place for the next generation.

How do you decide what variety/crop is appropriate for the microseason? Can you give us an example of a past mailing and how you selected the rice?

The ways in which rice can be described has great depth and breadth. At this early stage in rice education however, I have opted to simplify the communication. Currently I am using a simple double axes graph to plot where the rice varietal sits in relation to other varietals. The axes are “dense” to “light” and “soft” to “firm”.

For the season “Heavy Snow”, 7 – 21 December, I chose three varietals that lean toward dense and firm. As the shortest day nears, we tend to prefer richer foods. So while having dense rice with a toothsome chew is welcome, the al dente quality of a firm grain balances well with dishes that may be more heavily seasoned.

Eventually radar charts, tree diagrams, sunburst charts, and other infographics will be offered. But I prefer to start simple.

Love rice? Subscribe to Kiki Musubi’s 24 seasons of hand-selected rice here or attend the upcoming Spring Micro-Seasonal Dinner Gohan with Rice Girl in Tokyo on March 25, 2018.