The Geographic Dispatch critically examines issues in our global food system in ways that transcend space and place.

The local food movement has promised to disentangle ourselves from the ills of commercial agricultural production. At the movement’s core is the notion that what is far away is out of the control of our communities and produced without the regard for our needs. Non-local foods are implicated in mass-produced monoculture. They are tied to human rights abuses in the pursuit of raw materials and additives to reduce production cost and yield a greater profit. As Alicia Kennedy writes on cheap, processed peanut butter: the violence of extracting palm oil from Liberia typifies the way the global food system plunders and exploits the “Global South to feed the Global North.”

And yet, “local” foods are not devoid of sins. When the local food movement prioritizes geographic proximity over deep understandings of political ecology, it can still allow for deeply unjust practices such as sourcing food from prison labor. Considering geographic proximity alone will not free us from reliance on plantation ecologies rooted in racial capitalism and environmental destruction. Over 30,000 prisoners, overwhelmingly people of color, are working in the food system in the US, and with increased policing of the American borders and deportations of undocumented immigrants, the food system’s reliance on prisoners may continue to grow. This isn’t the future of food that we want. So how can we imagine new ecological futures that stretch beyond thinking about the local? How can the local attend to social justice and sustainability?

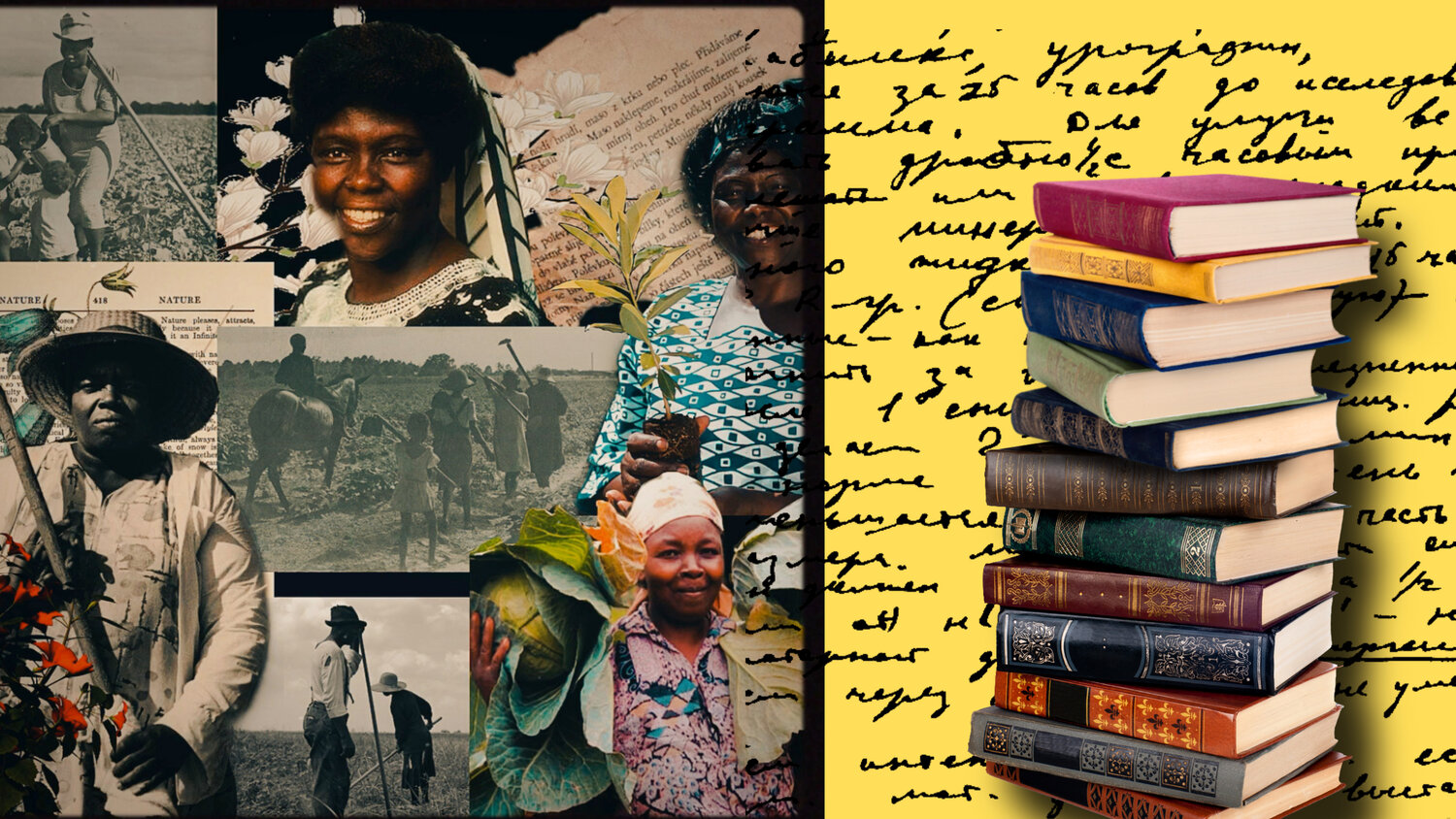

A critical geographic perspective can help us consider the ways “local” foods can be intricately tied to national and global processes—and not exclusively harmful ones. Foods can be local and fed nitrogen fertilizers produced by a distant manufacturer. Foods can be local and are only made available to or exclusively speak to a small subset of the population. One of the many ways we can expand the local food movement to attend to racism, white-supremacy, and social inequity in our food system is by thinking with Black ecologies.

Freweyni Asress, the curator of the popular Instagram account @Zerowastehabesha and a community organizer based in Washington, DC, strives to inspire followers to think with Black ecologies. When she originally started the account in 2016, she sought to document her new, zero-waste lifestyle. During the course of her studies and her increased engagement with notions of environmental justice and neocolonialism, Asress began to shift the account’s focus toward compiling an archive of Black ecologies and encouraging online, communal study of Black indigeneity, anti-imperialism, and anti-colonialism.

While Black ecology does not have a single, strict definition, academics J.T. Roane and Justin Hosbey have described it as a “way of historicizing and analyzing the ongoing reality that Black communities in the US South and in the wider African Diaspora are most susceptible to the effects” of environmental crises. It also suggests that the knowledges produced by these communities can help inform new political interventions and ecological futures.

“For me personally, my entry point to Black ecology wasn’t theory, but rather just how I was understanding and learning about my and my ancestors’ relationship to the land. I wanted to understand the state and institutionalized violence that Black people and our ecologies are experiencing as well,” says Asress. To think with Black ecologies is to not see “food deserts,” but instead see food apartheids; to upend the tendency in urban ecology to depoliticize our environment and see the ways power and racism are at the core of our built physical world.

Thinking with Black ecologies allows us to see how Black people differentially experience access to food, the institutionalized erasure of their food knowledges, and how environmental movements (especially in the US) exclude Blackness. “Black ecologies is also a love language,” says Asress. “When I think about Black ecology, I transport to my grandmother’s farm in Gonder, Ethiopia. I am picking tomatoes and maize with her as she tells me stories of my mother and how much she loved gardening.” The posts on @zerowastehabesha expose followers to environmental justice reading lists, bite-sized portions of academic thought on black geography, and Black indigenous culinary culture—including traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremonies.

My entry point to Black ecology wasn’t theory, but rather just how I was understanding and learning about my and my ancestors’ relationship to the land. – Freweyni Asress

Not only is Asress using Instagram as a platform for informing people about how to rethink environmental movements, she also conducts online workshops. Her most recent workshop introduced participants to Black ecologies alongside other public intellectuals of social media. By cultivating a space where Black people can engage with such thinkers as Angela Davis and Ashanté M. Reese, Asress goes beyond striving for a “seat at the table”: “My focus is making sure my people are freed.” Anti-Blackness permeates our global food system in its plantation model, its reliance on prison and slave labor, its dumping of waste in marginalized communities, and its violent expropriation of indigenous lands. Black ecological thought suggests that environmental crises can only be solved through the decolonization of Black people.

What does the cultivation of Black spaces in the local food movement look like outside of cyberspace? Perhaps it looks like Community Services Unlimited (CSU) based in Los Angeles. With roots in the Southern California Chapter of the Black Panther Party, CSU manages what it calls a “Community Food Village project,” including a minifarm located in a predominantly Black and low-income neighborhood. Their food distribution program and cooking classes are organized by volunteers based in the community. Crucially, this food justice organization sidesteps the white-centered narratives commonly associated with community gardens. As Hanna Garth writes in Black Food Matters, “CSU’s holistic approach to food as part of community empowerment, self-sufficiency, and Black and Brown diasporic solidarity casts ‘healthy’ not as a proxy for the white middle-class American citizen but as a form of healing communities of color through food.” It centers Black culinary culture—including so-called “unhealthy foods”—rather than “merely inserting Black people into white spaces.”

How can race be incorporated into design thinking? This is the subject of the online seminar series “Race, Ecology, and Design” hosted by The Ecological Design Collective, a new online and (eventually) in-person forum dreamed up by a group of academics, thinkers, designers, and activists. Sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic and its highly differentiated effects, the group strives to become a collaborative space to reflect on “the exclusionary nature of our capitalist present, the harsh legacies of racism and colonialism that have long condoned the exploitation of societies and environments elsewhere” and imagine new ecological futures that are grounded in “listening and responsiveness.”

To become a part of the conversation, follow @zerowastehabesha on Instagram, become a member of The Ecological Design Collective, and dive into the Black ecology reading list at Bilphena’s Library.