Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

If you’re anything like me, our televisions and social media feeds are constantly buzzing with the background noise of cooks and food personalities that have found fame through an on-screen persona, a knack for storytelling in their bestselling cookbooks or a curated Instagram grid. But if you’ve ever stopped to think about the names that changed food history, that influenced generations of cooks, consumers and institutions, you won’t find them uploading artful shots of their breakfast spread online. You might not even be able to find a single book about them – but with every discovery, act of reform or problem solved, comes a cook, designer or scientist that was there to shape it. They may not be the first, or even be successful in all of their endeavors, but will have played a vital part in the course of food history.

In 19th century England, it was Alexis Soyer, a French author, designer and chef who became the most celebrated culinary figure in Victorian England. Soyer redesigned British cookery and kitchens and underlined a certain charity of purpose for chefs through his ideas and publications. Born in 1810 in Meaux-en-Brie (a town known for producing Brie cheese), Soyer worked in kitchens around France from the age of 11. He then joined his brother in London in 1830, who was a chef for Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge.

Kitchen Design at the Reform Club

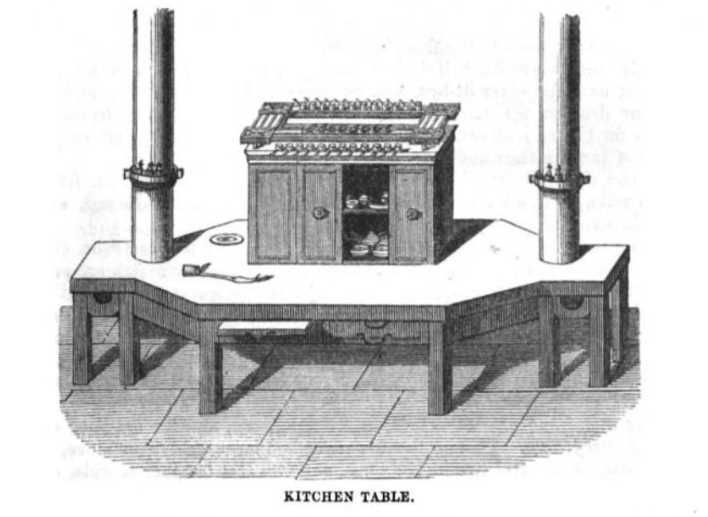

Soyer’s culinary career progressed, and in 1837 was appointed Chef at the political Reform Club—founded in 1836 as the headquarters of the Liberal Party. In the year that followed, Soyer helped architect Charles Barry redesign the club’s kitchens—his innovative design and use of British ingredients still inspires the menus today, and rightly so. He introduced gas cooking and adjustable oven temperatures to the kitchen, which improved the speed and consistency with which restaurants could serve food, as well as the comfort and labor of chefs. He even invented a “sink trap bell” which would catch food debris, preventing blockages in the kitchen sinks. In his 1846 book The Gastronomic Regenerator, Soyer also boasts of the table he designed for the center of the kitchen, which is enough to make any home cook drool:

“In the middle is an elm table, made on a plan entirely original, having twelve irregular sides, and giving the utmost facility for the various works of the kitchen, without any one interfering with another…there are two columns supporting the ceiling and passing through the table, round which, at a convenient height, are copper cases lined with tin, in ten compartments, each of which contains every ingredient and chopped herbs of the seasons for flavouring dishes…”

Philanthropy and Fisherman’s Food

Soyer wasn’t only celebrated for his innovation and creativity in restaurant kitchens; his life’s mission proved to be providing accessible and nutritious food to those without the resources of the professional cook. He was appointed by the government to provide relief in Dublin during the Great Irish Famine of 1845-49.

While there, he not only opened purpose-built soup kitchens but also wrote and published Soyer’s Charitable Cookery: or the Poor Man’s Regenerator (1848). The booklet included 23 recipes that focused on reaping the benefits of underappreciated vegetables, readily-available meat and fish, and starchy (or farinaceous) ingredients—for example his soup that calls for any “solid meat”, root vegetables such as onions and turnips, pearl barley and water—thickened with flour. Other recipes provide a Fisherman’s Food for the Coast, using “any kind of cheap fish” stewed with leeks and covered in a flour batter. Soyer reassures readers of the versatility of this meal, writing that “the same receipt may be used in a pie-dish and baked.” One penny of every copy sold went to raising funds helping the poor, and he describes the book as “a small pamphlet…which might prove useful to humanity at large, [the recipes] having the great advantage of being very cheap and easily made”.

Upon his return to London, the now celebrity-status chef, philanthropist, writer and inventor continued to focus his attention on teaching the public resourceful methods of cooking. Food historian Pen Vogler claims that this was one of many reasons he became so popular amongst the British:

“He showed housewives how to repurpose and reuse food, which was something the French were very good at, and the English had a reputation for being terribly wasteful.”

A Culinary Campaign for the Crimean War

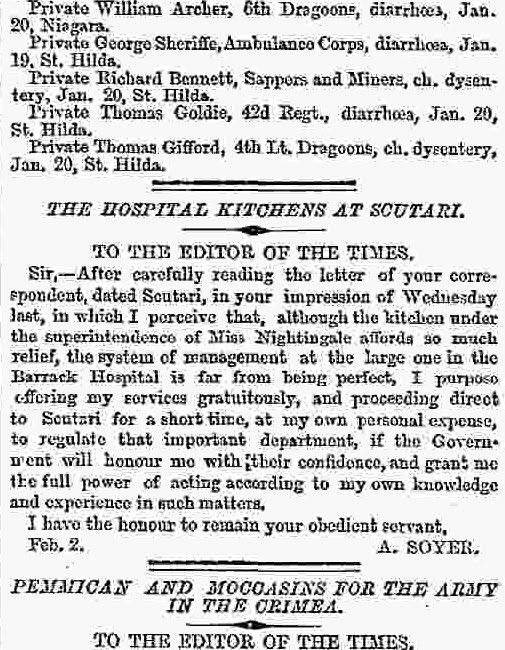

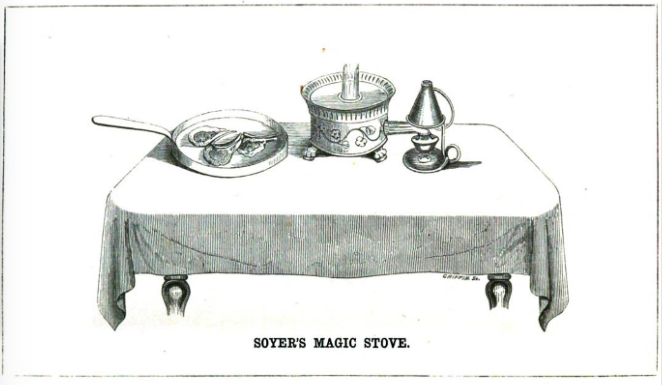

Soyer’s concerns were also growing for the poor health of British soldiers fighting in the Crimean War. After writing a letter to The Times in 1855 offering his services, he travelled to the Scutari Hospital, where he worked to improve catering for British soldiers. Already the inventor of the “Magic Stove” which could be fueled by any household spirit, Soyer developed the field stove, which could withstand all weathers, save fuel and provide warmth. Working with Florence Nightingale, he also upgraded hospital and camp kitchens, and transformed daily regimes and recipes to improve nutrition.

Upon surviving the war and returning to England in 1856, he published his own Culinary Campaign: With the Plain Art of Cookery for Military and Civil Institutions, the Army, Navy, Public, Etc., Etc. giving a detailed account of his work and how it could be adapted to continue improving food. However, his health had deteriorated from his experience, and he died the next year aged 48. Soyer’s Stove remained in use by the Army for another century, ensuring access to cooked food and warmth in treacherous weather conditions.

Alexis Soyer’s letter to the Editor, in The Times 3rd February 1855, placed under a list spanning two columns of reported deaths from illness.

Soyer wasn’t without fault, his entitlement and status-seeking supposedly causing issues in his career, especially at the Reform Club. After resigning from his role in 1850 and desperate to extend his spot in the limelight, he launched a range of products emblazoned with his name and face, including “Soyer’s Nectar”, which he claimed cured hangovers. A year later he opened his own culinary venture, Soyer’s Gastronomic Symposium of All Nations, an extravagant multi-sensory experience situated across the road from Hyde Park, aiming to catch footfall from the Great Exhibition. The project, although spectacular, was overly ambitious and closed just months later with huge financial losses.

The French chef was not the first to play a part in the reinvention of Western cookery, nor to dedicate his work to delivering aid to those in suffering, but he is an individual that worked tirelessly for the future of food. Soyer considered the location, function and design of every element of the kitchen, to improve output of not only established restaurant kitchens, but also makeshift hospitals and home cooking – his problem-solving designs, gas stoves, and utensil and ingredients storage providing a template for what would become the modern kitchen. He knew that the issues in our food quality and health stemmed from class segregation, and inaccessibility of education and resources, promoting “wholesome and digestive food, which…Nature has abundantly produced” (Soyer’s Charitable Cookery).

There are countless lessons to be learned from not only this man’s endeavours into social reform, but also the contexts in which he worked. To become inventors of a sustainable, fair and enjoyable food system no part of eating can go ignored. From ensuring that the most vulnerable members of society are fed, to understanding the importance of a party and sensory indulgence, the role that food plays in conjunction with science, art and design, and ways in which we can improve health, wellbeing and living conditions.