Communal ovens are an ancient tradition that have served as the lifeblood of rural communities around the world. From medieval France to modern-day Morocco, wood-fired ovens shared by several households do more than feed many mouths—they also forge deep ties amongst neighbors. This is true in El Salvador as well, where public beehive ovens serve as the cooking source for families to bake bread in the morning and braise meat throughout the night. The Los Angeles-born artist Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s father grew up in San Miguel, where he constructed many of these beehive ovens, as he was adept at making things from a young age. This personal and cultural history is one of the main inspirations for Aparicio’s Pansa del Publico, a 6,000-pound brick oven coated in ceramic spikes that currently resides within the Los Angeles State Historic Park.

For Aparicio, the functional nature of the sculpture is foundational to the work. And so he’s partnered with Occidental’s art hub Oxy Arts and the public art organization Clockshop on a series of collaborative events with activists, writers and local chefs who are also second-generation immigrants, such as the Armenian-American baker Kristine Jingozian and the Salvadoran-American caterer Michelle Lainez. The inaugural activation featured Lainez, who used Pansa del Publico to fire up traditional Salvadoran quesadilla, a fermented cheesy pound cake, followed by chicken marinated in chiles, seeds and dry spices and cooked with tomatoes and onions.

“The history of Western art is this idea of appropriating aesthetics from other cultures but removing the functionality from it, and that was something I wanted to reverse,” Aparicio said during a hot June afternoon in the Chinatown park. “I wanted to make public art that elevated the gesture of cooking as an artistic act.”

Attendees of the activation munched on crumbly slabs of quesadilla, sipped icy-sweet horchata and waited for the braised chicken to finish cooking over almond wood as Lainez explained how communal ovens operate in her home country. “Every town has a mill and every few houses has a huge oven that’s shared throughout the day. Once everyone has baked for the day, that’s when the guisados (the braises) start. The ovens are never not warm,” she said.

The history of Western art is this idea of appropriating aesthetics from other cultures but removing the functionality from it, and that was something I wanted to reverse

Pansa del Publico marks the first time Aparicio has collaborated with cooks, but it likely won’t be the last. “The way that certain chefs in LA are thinking about food and where it comes from— being super specific about materials, relates closer to how I think about art than a lot of the artists that I’m friends with,” he says of the kinship he’s found with local chefs, especially other second-generation immigrants. His focus on working intuitively with locally sourced building materials to express complex notions of Latinx identity mirrors how folks like Lainez and Jingozian utilize local ingredients to create their own spins on traditional dishes. “We’re talking about how we don’t [necessarily] need to go back to our home countries to get a specific brand, we can find it here and then interpret those recipes in ways that make it current to our own experience,” he says.

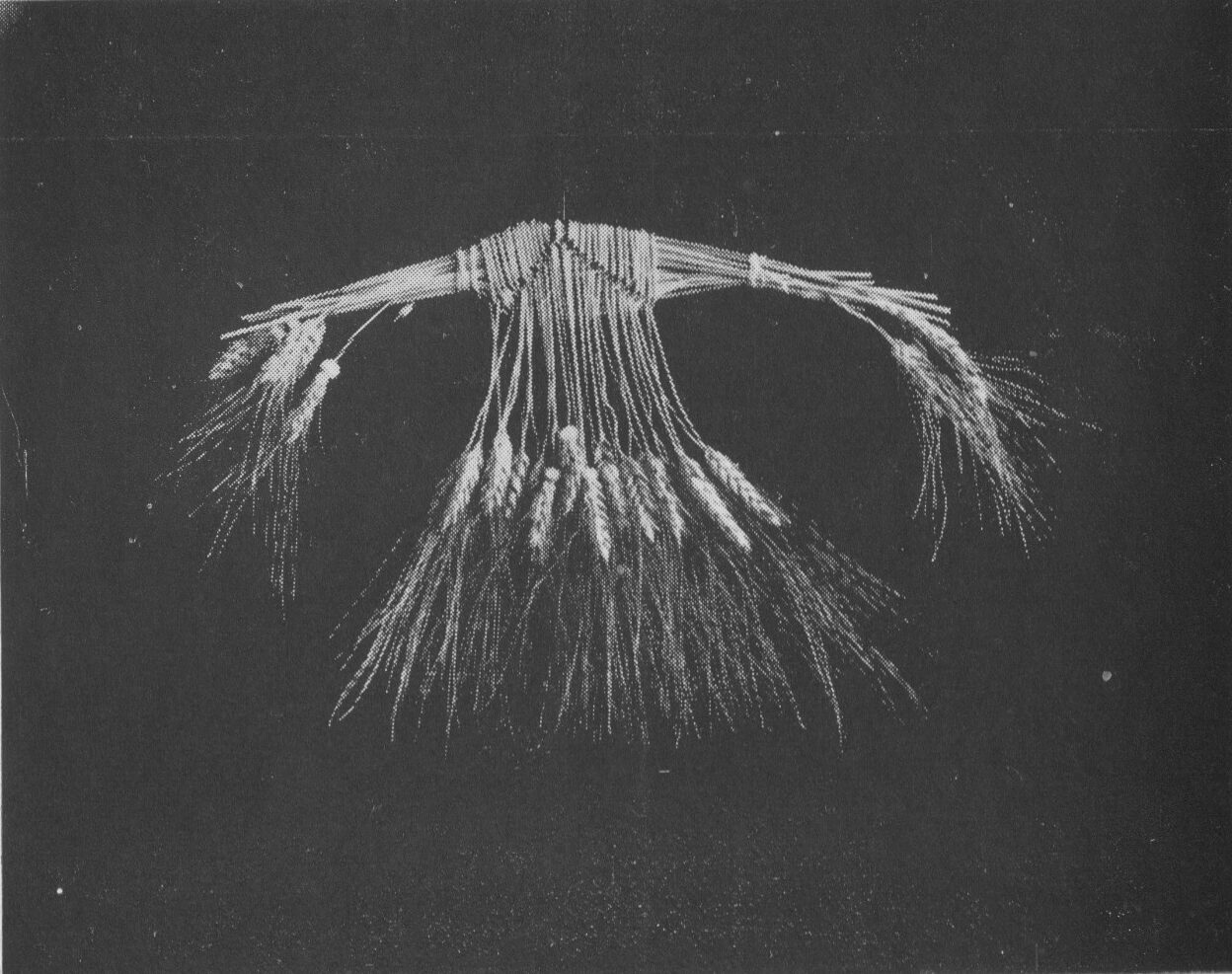

As a body, Aparicio’s work explores issues of immigration through the conceptual possibility of materials. He draws connections between his ancestral Central America and native Los Angeles, in turn advocating for an expanded understanding of Latinx identity. The bricks that line the inside of Pansa del Publico represent those that were used in the construction of the Zanja Madre, the first aqueduct that brought water to the Pueblo de Los Angeles in the mid-19th century which was essential to establishing the Spanish colonial settlement. On the outside of the piece, the ceramic spikes are a reference to the sacred Ceiba tree of ancient Maya, which grows horns to protect itself. In this sense, Pansa del Publico is an attempt to preserve indigenous tradition and celebrate community connection in a city teeming with dynamic diasporas.

Like many of us, Aparicio spent a good portion of the pandemic at home making bread. Unable to access his studio downtown during lockdown, he also turned the back of his house into a ceramic workshop. The parallels between baking and art-making that presented themselves during this time spurred a revelation for the artist. “I was rolling out the clay and then I’d go roll out the dough. And then I put the clay in the kiln and bake the bread,” he recounts. “And I was thinking about all of these artistic elements that are in our everyday gestures.” He remembered how he used to watch his parents cook and fold clothes and saw an opportunity to create something with utility, from the perspective of his family’s lived experience. “It’s a much more interesting way to engage in sculpture,” he says.

Pansa del Publico is also influenced by the artists, activists and chefs who have utilized their platforms for mutual aid in response to the hardships brought on by COVID-19. Drawing a link between the ways Angelenos have mobilized to feed their communities and how Salvadoran immigrants used to sell food in public parks to send money back to loved ones entangled in the Salvadoran Civil War, the sculptural feat centers the resilience and power of collective organization. Like the oven, which maintains its high heat for lengthy periods, the immigrant struggle for cultural and economic survival is a force that doesn’t die out. The first time Aparicio put Pansa del Publico to use, he got it up to 900 degrees to make pizza for the park staff. When the artist returned to the site two and a half days later, he was surprised and overjoyed to find that the oven had retained its fervor: “It was still at 700 degrees.”