This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 02, A Seat at the Table. Order your limited edition issue here.

Martí Guixé is opening a bar. Twenty years after he lobbed the explosive idea of designing food into a conservative industry defined by chairs and lamps, the Catalonian industrial designer is returning to the site of his most iconic project with another provocative concept that speculates on the future of design. Guixé’s L’Ex-Designer Project Bar is a bar that doesn’t sell drinks. In fact, from his perspective, the Bar doesn’t even need to be open to customers for it to be viable. “You could see it on the Internet and look at the projects, but we have it open because we are from an old-school generation,” he explains, wryly.

A sketch shows the interior of L’Ex Designer Bar.

A sketch shows the interior of L’Ex Designer Bar.

Guixé might joke about being “old-school,” but his body of work over the last 20 years can be understood as a dogged, critical investigation of the potential future and limits of industrial design. His work has been so misunderstood, that in 2001, the designer began self-identifying as an “ex-designer” as a way to free himself from the expectations of the design community. “The idea was to do work in design in a different way,” Guixé remembers. “An ex-designer comes from a design background but is not designing in the specific. Instead, you are designing more freely or because you like it—like an ex-tennis player who still plays tennis, but for fun and not for competition.” Within today’s context where the spectrum from UX, systems design, to synthetic biology, fall under the umbrella of design, this idea seems hardly revolutionary. But in 2001, product design removed from the grips of industry seemed almost unimaginable.

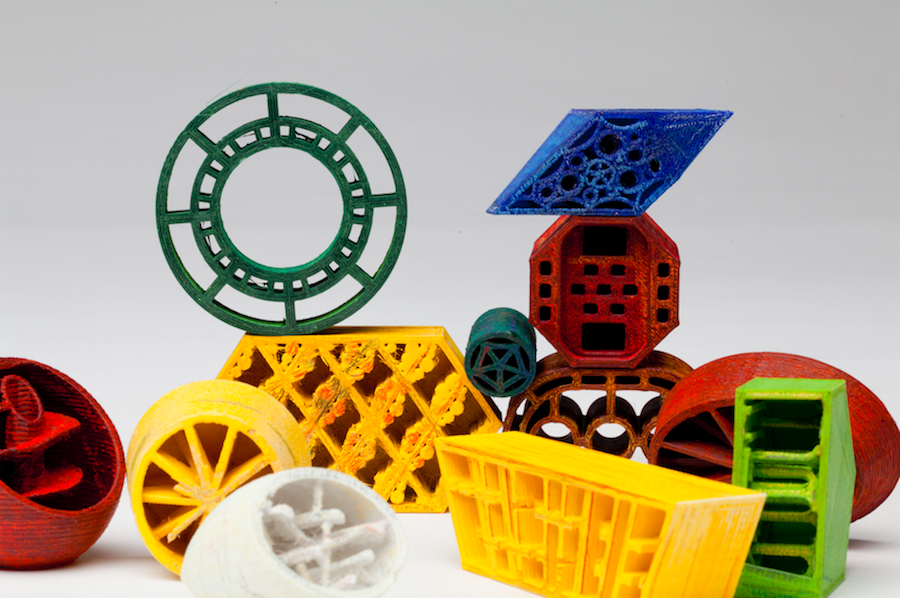

The interior and all the objects for use in L’Ex Designer Bar will be 3D printed, including the food.

The interior and all the objects for use in L’Ex Designer Bar will be 3D printed, including the food.

As an ex-designer, Guixé’s projects examine the design process and its interplay between production and business. The products developed through this investigative process tend to be new typologies for familiar objects (with instructions for how to engage). My first encounter with Guixé’s work embodies all these values—at the 2001 Workspheres exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he presented a vending machine full of speculative pill-sized products. HiBYE 7.0 enabled best practices like, “write everywhere,” “carry nothing,” “give memory gifts,” and “consider everywhere indoor,” for the nomadic worker.

Martí Guixé’s HiBYE installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Martí Guixé’s HiBYE installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Guixé is widely credited with introducing the concept of food design to the world when, in 1997, he opened an exhibition of photographs from his project SPAMT: Techo Tapas with a largely unplanned bit of performance art. As he tells it, the gallerist was concerned that the public would ignore a design exhibition without design objects. The gallerist “insisted that I should prepare [one of the SPAMT concepts], this tomato with bread inside, but I don’t like cooking.” Guixé didn’t want to do it so he asked four friends to come and help him prepare the snacks. Before they got too far, the gallerist interrupted the assembly line and told the motley crew that they had to assemble the edible objects in front of guests, as part of the opening. The response was swift and overwhelming.

20 years of food design with ex-designer Martí Guixé.

20 years of food design with ex-designer Martí Guixé.

Spanish newspapers and television covered the performance aggressively. “It was really radical because we were touching an icon, and there is a political layer,” Guixé remembers. By redesigning pa amb tomàquet, the most representative dish of Catalonian cuisine, he touched a live wire of culture while testing the boundaries of design. In typical Guixé fashion, he joked, “a lot of magazines did great reports but with really bad critics.” From this initial foray into the field of food design, Guixé began staking out the larger territory of ex-designer. The term subverts critics who tried to label his work as “art” by clearly embracing his role as a designer, but one that operates in a different context.

Tapas-Pasta is a system designed to cook pasta so that it can be eaten like tapas.

Tapas-Pasta is a system designed to cook pasta so that it can be eaten like tapas.

This context is established through a radical shift in thinking about the role of the designer. An ex-designer “proposes the ‘business model’ as a new artistic discipline,” the L’Ex Designer project website states. Early projects included 2005’s Food Facility, where diners were invited to peruse the menus of local take-out restaurants, place an order with a “food advisor,” and enjoy the delivered meal, plated and served in the ambiance of the prototype restaurant without a kitchen. Or 2004’s interior commission for the Spanish fashion retailer Desigual where the designer took his budget, threw a private party and invited his friends to come and paint the space on the eve before the store opening. The Project Bar continues this line of inquiry by investigating what it might mean to remove the business of selling drinks from the concept of a bar. Instead, the bar becomes a beacon for people to gather. As Guixé explains, “that way, you have people you can organize and do things with.” The bar as a “point of interest” has resulted in two years of programming ranging from concerts to “food sessions,” and networking nights hosted by designers.

An event for Guixé’s L’Ex Designer Bar.

An event for Guixé’s L’Ex Designer Bar.

The idea for the Project Bar started from a plan to 3D print the tomato and bread SPAMT, a return to the beginning of his 20-year exploration of food as an industrial object. “In the ‘90s, I was very interested in mass production, and that’s how I came to food,” the designer told a crowd at Design Indaba. “Because food is a very mass-produced thing, but nobody sees it as an object.” Set in the same gallery space where he introduced the world to the concept of food design 20 years ago, the L’Ex Designer Project Bar is also a return to Guixé’s prodding interest in design as a tool for production.

The I-Cakes project uses a pie graphic to represent the ingredients of a cake in percentage form.

The I-Cakes project uses a pie graphic to represent the ingredients of a cake in percentage form.

3D printing is a critical outlet for Guixé’s exploration of production and process. The Project Bar is a work in process where everything is being 3D printed—the bar and all the barware including drinking glasses, plates and utensils. Uninterested in artisanal craft production, he sees design, “as a tool to simulate the process to mass produce a product.” 3D printing technology enables small-scale production and the introduction of unique elements, but products are still being produced with the aid of a machine and can be scalable. “Mass production, since five years [ago], is not manufactured for a human center, but for an economic purpose,” Guixé warns. “Most things are not ecological or are not necessary. A philosopher in Barcelona compares industrialization with world war in terms of damages and the environment. Microproduction takes advantage of the knowledge of mass production.”

Guixé’s 2001 I-Cake’s project.

Guixé’s 2001 I-Cake’s project.

The project kicked off in the empty gallery space on November 5, 2015, with an expected duration of two years from the first tile to the last 3D printed tomato. As of press time, the studio is still printing the bar with no specific timeline for when the performance might come to a close. In the meantime, visitors can stop in, purchase packs of the 3D printed drinking vessels, and even grab a drink.

Concerning food design, 3D printing offers an entirely new window into thinking about what and how we eat. Mass produced food in its current form is not healthy, the designer explains. 3D printing technology enables one to reimagine manufactured food, “as an architectural element with different vessels and with containers inside with structures. You don’t need to go to the old process of cooking and molding. You can really build it,” Guixé predicts.

Digital SPAMT is produced by a 3D printer.

Digital SPAMT is produced by a 3D printer.

Although today’s 3D food printing technology lags far behind Guixé’s vision, his studio is experimenting with new typologies for future foods aided by the tools of microproduction. For this year’s groundbreaking Food Revolution 5.0 exhibition at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MKG), Guixé introduced “Digital Food,” a speculative project that is a fully customizable “feeding system” that produces foods configured along the inputs of nutrition, active principles, construction and gastronomy. “In a way, ‘Digital Food’ is an end of my process of 20 years,” Guixé reflects. “But until 3D printing technologies are more advanced, we will not be able to advance this idea of design as I imagine it.”

An event for L’Ex Designer Bar project by Martí Guixé.

An event for L’Ex Designer Bar project by Martí Guixé.

Until then, the designer is celebrating two decades of practice in the same way that he started it: with some humor, and surrounded by friends. The logo marking this anniversary is two crossbones and a slingshot inscribed with the words “design power.” If his logo is any indication, 20 years of food design exploration doesn’t mark an ending, but a new opening to sling a few rocks into the crowded field of design.