Priya Mani is a Copenhagen based designer and cultural researcher who explores and writes on migration, food, how people use everyday technology, and digital democracy in emerging economies.

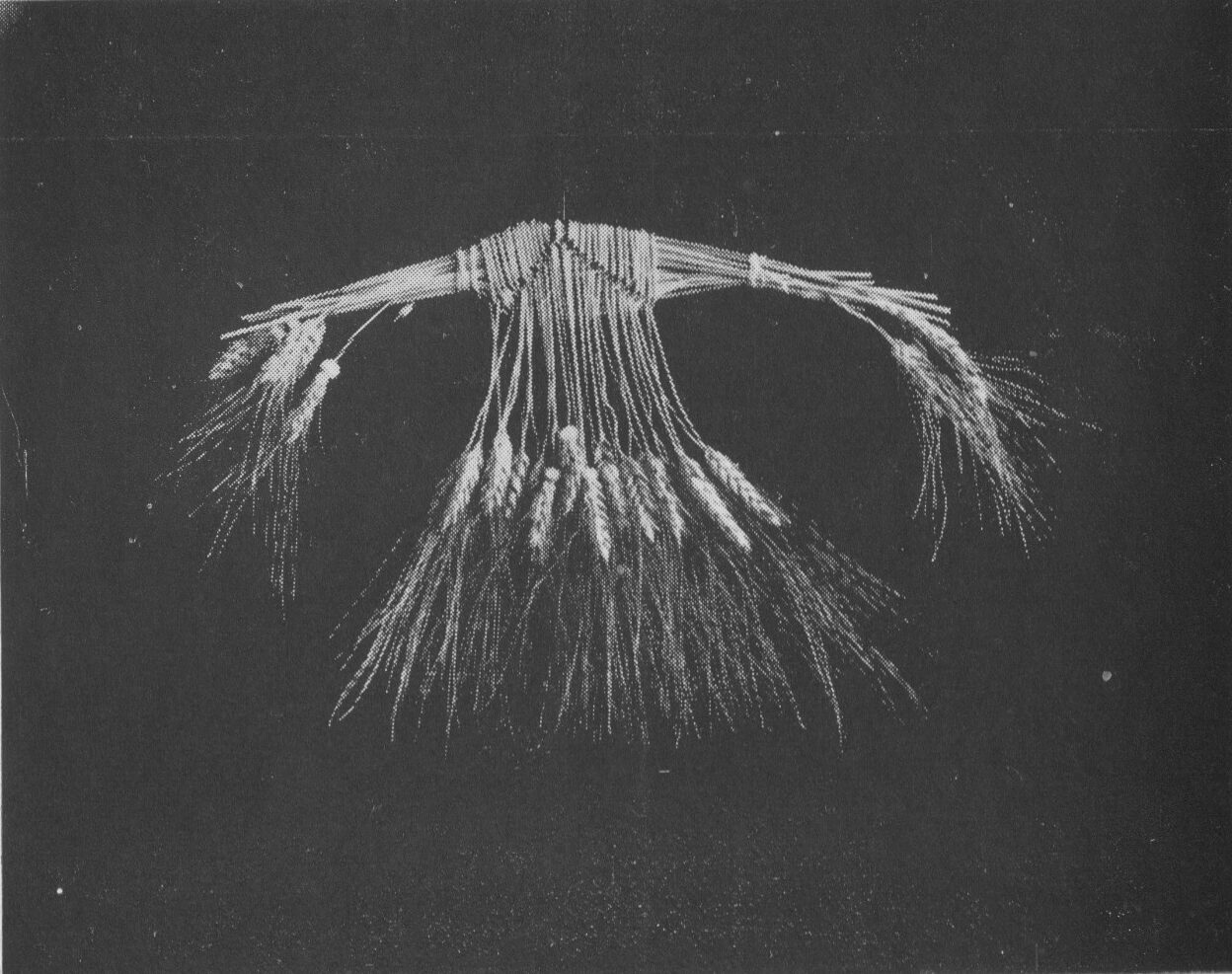

Through her Instagram, Cookalore, she is cooking a “Visual Encyclopedia of Indian Food from A-Z,” exploring concepts, ingredients and preparations that are unique to the mainstream narrative of Indian food—its cultivation, preparation, consumption, myth and mythology.

As this project progresses, it nudges participants and viewers to think about what an A-Z of Indian food could mean for them, where they are, how their communities and family have come to be, and what they envision as their own narratives of Indian food.

Elizabeth Yorke:

Why did you decide to start this project?

Priya Mani:

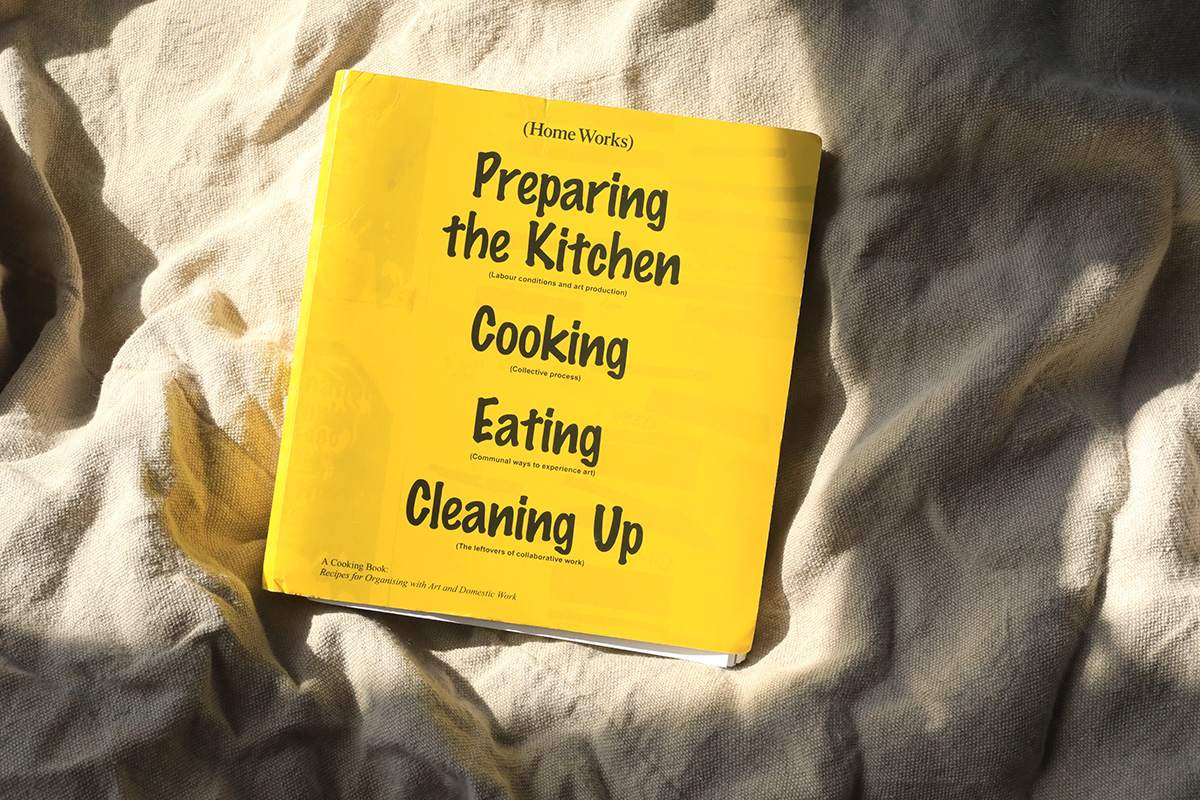

Eating is crucial. To cook and eat, there are recipes. Eating—the consumption of food—is the most basal of our needs, and as we go up Maslow’s pyramid, the more we think and write about food makes the subject an intellectual space, and this medium for discourse.

I was having conversations with people from the Indian subcontinent and in the diaspora who were interested in food—people who were cooking food and using recipes from there. The ingredients themselves were huge points of discussion based on where you came from—how you cooked with it, why you didn’t cook with it, how much of it was used, how it figured in your diet, did it speak of class or culture? So many conversations were being had, and were to be had.

For many years Achaya’s works, particularly the Illustrated Foods of India was a quick reference I kept in my kitchen. But over the years I have felt a lacuna for supporting visual references, broader spatial coverage and annotations of cultural references, as I think food and culture are inseparable.

I started to think about seasonality as a way to begin this project but cooking A-Z seemed more fun and nerdy and made me push myself to look for things because it belongs to a certain alphabet.

EY:

How do you see the current narrative of Indian food culture evolving?

PM:

We are beginning to see a lot of food writing in the regional cooking space. I also find hyper-local blogs in vernacular languages which are very honest and fun to read and/or watch the videos.

We also see that some of the regional food writing tends to generalise the food and ingredients to the region. The reality is always more mosaic than that. In order to understand food in India, one has to include caste, religion and culture. It does not have to be hierarchical, but these coordinates put the food in context. In some cases, this allows for a more nuanced dialogue on cooking techniques, which is crucial to understand.

I also find that some of the important voices coming out of India in this space write about food with a specific tone: they write about people and communities who are shamed for their food, about suppression of their food cultures, about not being represented. While this is important, we are also in a moment in time which can offer more equity. As I cook through a diverse cuisine, I find food to be incredibly unifying too, “Same same, but different”.

In basil I found that while it is the holiest for the Hindus, the seeds found their perfect recipe in the Persian-inspired cold dessert, falooda. Every religious group in Kerala has an appam to their claim; the fermented rice and coconut milk pancake unifies society in places where politics divide.

EY:

Where and with whom do you think the scope lies for inclusion of often left out narratives in food media/design?

PM:

I see a huge upsurge in the documentation of local foods. This is great, because we are finally seeing more local voices. Youtube videos, blogs and Instagram are powerful tools—they connect these hyper local voices across the globe. This is fantastic as they know their nuances best. I also hope that some of these videos continue to get made in vernacular languages. Blogging about foods from other cultures for the sake of blogging, with half the ingredients replaced or the techniques altered, seems futile and like a lot of noise in the space. And there is a lot of noise in this space—filtering it out and extracting meaning itself has become a strong pursuit.

EY:

How has the experience been creating work about India outside of India? What has it been like to source ingredients and tools?

PM:

The global lockdowns and rather unsafe situation in India has meant my parents have found it a bit challenging to source ingredients for me. But all the same, since I cook all the food in my encyclopedia, I manage quite okay. Sometimes I just have to make ingredients from scratch that we take for granted in India like khoya or axoni. It allows for a certain appreciation of time and space. Some other ingredients have been easier to source than it might have been back in India, especially high altitude, temperate ingredients like ashwagandha, fiddlehead ferns, cannabis or angelica. In some sense, it has also surprised me how globalised the world has become.

EY:

The visuals that you create are stunning! What are your thoughts on the impact food design can have on the narrative or interpretation of “Indian food”?

PM:

Food design is extremely important especially to the visual narrative. We need to somehow come out of the cliche of loud, cluttered plates and brown gravies, foods doused in garam masala or tadka and hing (asafoetida) in everything. In reality, if you dig into the details of exceptional versions of something you have tasted, the cook has done something thoughtful. I see our food as vibrant and bold, yet simple. We need to be able to transfer that idea on the plate and the image. It’s also important to represent food in a well thought out visual discourse that is simple yet deeply representative of the food, and perhaps more importantly, shed the baggage of stereotypical food photography.

For the visuals I create, all the research I have done for the story of the ingredient or the preparation informs my image. In some cases, if I don’t find appropriate props, I take time to create them too.

EY:

Which ingredient/recipe/tool so far has been the most challenging to create or research around and why?

PM:

I really didn’t expect my Apong story to rake in that interest. Apong is a rice beer from the Mishing tribe of North East India that is made with a cake of special rice and e’pob, an herb-based starter, that ferments the cooked rice. As a process, it was very challenging to brew the apong from the three e’pob starters I had received because we were in the thick of winter here in Denmark. Similarly, some posts have called for cooking many variations to show a broad spectrum like with the appams or anarsa, a rice flour-based biscuit—those are intense days in the kitchen.

Finding blue agave wasn’t easy either. After months of searching for one and thinking about how to make it happen, I found someone selling a palm tree on our local Ebay. In the picture they had posted I found a massive blue agave in the background. I texted the guy telling him about what I was doing and if he would be open to letting me photograph it. He was so kind to let me do that. On Easter Sunday, two hours before he was hosting a family gathering, we drove out to him, an hour from Copenhagen. What I saw left me in disbelief: his backyard with a swimming pool and palm trees looked like Santa Clara and he had a human-sized blue agave in a glass-covered porch. Unbelievable! Right here, in Copenhagen. It also turned out, he was a chef!

It is always fun to see which stories excite people. I think cooking through the entries has been very benefitting. It helps me see previously unthought connections, shared culinary techniques and cultural connections.

EY:

How do you see the future of this project you are building?

PM:

I hope I am able to really cook all the way through to “Z.” Many people have suggested it should be a book. I don’t know about that yet. As the momentum builds and more people are joining me in telling their part of the story, I think a path will evolve.