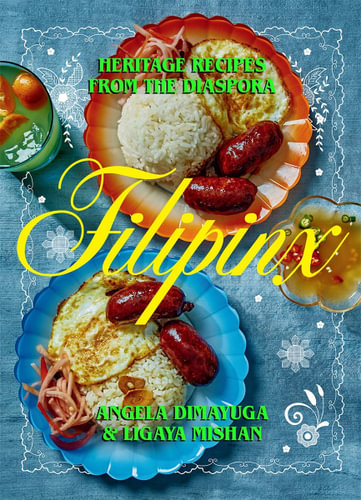

Robert Rauschenburger, medium rare, with a side of Kimchi Gordon, Shigeru Banchan Two Ways and a satisfying dessert of Rem Brûlée. Top off your night with a Lina Bo Bacardi Cocktail featuring cachaca, basil and cane sugar as a nod to the Brazilian designer’s “lush, expressive scenography.” Whether this sounds like a menu for the dinner party of your absurdist dreams, or its sending you into a tizzy of pun-tastic possibilities, Le Corbuffet, a new cookbook featuring 60 recipes with names like Quiche Haring and Lucy Orta Torta, is a riotous homage to the art and design of cooking and consumption.

Lee Krasner Dessert Moon is a trio of sorbets inspired by “the vivid intensity and jagged rhythms of Krasner’s collage through the sweet fruits of the earth.”

Lee Krasner Dessert Moon is a trio of sorbets inspired by “the vivid intensity and jagged rhythms of Krasner’s collage through the sweet fruits of the earth.”

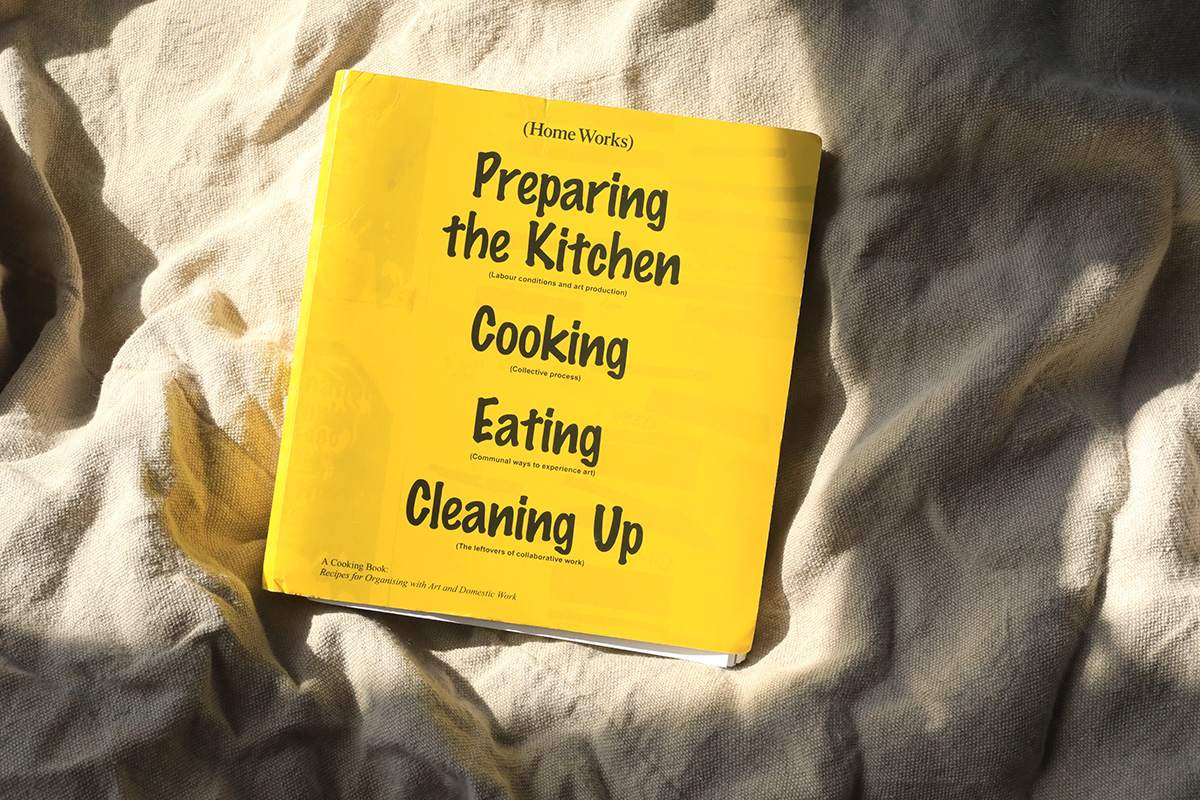

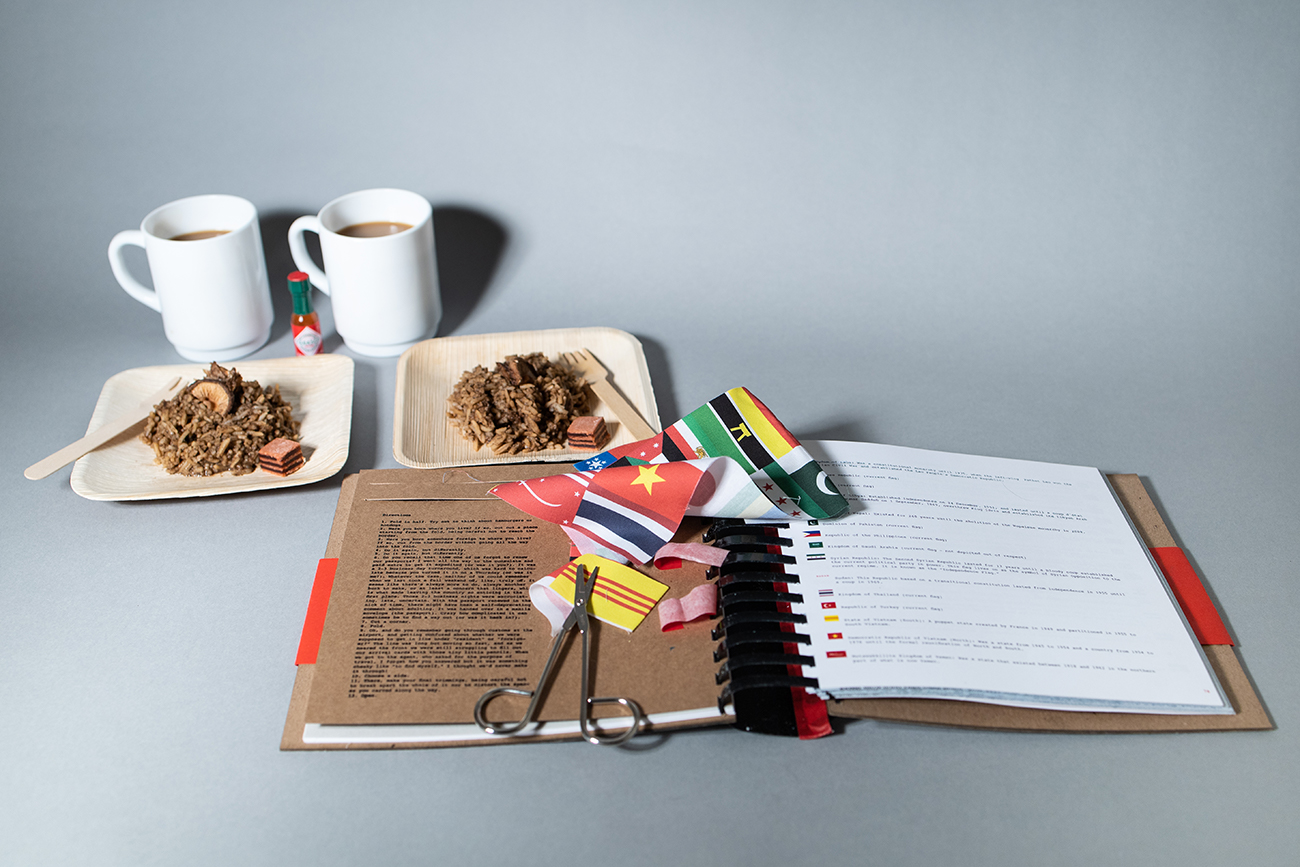

Le Corbuffet is the newest addition to a long line of artworks that serve as a cultural critique in the form of a cookbook. Written and shot by architectural historian Esther M. Choi, each recipe riffs on a canonical artist or designer’s work and personal biography and is accompanied by striking sculptural still lifes composed with humble ingredients and kitchen tools. A recipe for Florence Knoll Rolls is illustrated with unadorned dinner rolls propped to look like the laid-back styling of the designer’s modernist sofas. Choi writes, “Only timeless dinner rolls would do for the legendary American architect and furniture designer Florence Knoll…As an essential functional element in your dinner composition, Florence Knoll Rolls can be transformed into virtually any dimension to add structure, organization and direction to the ‘total design’ of a culinary experience.” It’s these knowing recipe intros that combine biography and whimsical quips that make Le Corbuffet an essential conversation-starter for design-loving home cooks. Taking inspiration from the scripts of Fluxus happenings, the book design comes from New York-based Studio Lin. The type choices and layout of Le Corbuffet highlight the ways that recipes serve as a sort of participatory, iterative, and imprecise performance while Choi encourages improvisation through her prompts.

In advance of the New York launch party for Le Corbuffet at Archestratus Books on October 4th, Choi spoke with MOLD about the process of creating the book, the ways that cooking can be critique, and how food is political.

MOLD: What was so significant about the menu you discovered, designed by László Moholy-Nagy for Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, that it inspired you to start your own event series?

Esther Choi: When I found the menu, I was struck by how much this atypical document (or, at least atypical for a design archive) revealed about Walter Gropius’s social standing in the 1930s. During a period of interwar rations, he was dining on pouilly, salmon and lobster sauce with Britain’s glitterati. It made me think differently about the sociopolitical ambitions of the Bauhaus, which are often discussed in socialist terms— a narrative that doesn’t easily align with the coveted objects of the Bauhaus today, and, as it turns out, didn’t easily align with its former director, even back then.

This prompted me to consider how food carries meaning, and how it could be used as a medium to probe questions of cultural value. The idea of reproducing and consuming the art and design canon seemed funny to me, both as a critique of how historical narratives and artifacts become rarified and replicated, but also as a way to satirize how the global market consumes cultural commodities. There was something very appealing in the sheer absurdity and futility of mimicking these processes with edible foodstuffs.

This tart grapefruit Rem Brûlée, is “inspired by the architect who thrives on the unexpected…unites two dessert typologies—creme brulee and a citrus tart.”

This tart grapefruit Rem Brûlée, is “inspired by the architect who thrives on the unexpected…unites two dessert typologies—creme brulee and a citrus tart.”

The presentation of these dishes was actually much looser than an event series. I started making dishes based on art and designs puns and sent out invitations to consume them. Sometimes an “event” took the form of a casual offering at the dinner table (like, “please pass the Flan Flavin.”) In other instances the events were more organized, such as a small Corbuffet fundraiser I held for City Harvest in my apartment. Either way, I always thought of these gatherings as ways to sketch out some ideas in a participatory format, not some kind of elaborate presentation or formalized scheme. The idea that a furtive, critical gesture could take place in an everyday, convivial setting appealed to me.

Why did you decide that a cookbook would be the best vehicle to launch a social and cultural critique about privatization, privilege and consumption?

The cookbook as an artistic format appealed to me because of its innocuousness. Cookbooks tend to live in the domestic sphere of the kitchen, a place of both creation and consumption. Like art and design, food culture has similar tropes of high/low cultural valuation, suffers from privatization (hello, neoliberalism!) and has a particular image culture attached to it which tends to reinforce capitalist values. I wanted to explore how I could appropriate the conventions of cookbook publishing—and push against them—to consider how domestic spaces of hospitality and even food’s image culture could become platforms for probing more critical ideas.

Frida Kale-o Salad takes the infamous Mexican artist’s “piercing gaze” and translates it into a lush salad with green goddess dressing.

Frida Kale-o Salad takes the infamous Mexican artist’s “piercing gaze” and translates it into a lush salad with green goddess dressing.

What was your process like for identifying the canonical artists and designers you wanted to riff on and then determining the elements and form in the sculptural still lifes?

Since all of the recipes are based on puns of artists and designers or art/ design works, the process of selection was largely left up to the pun itself. There was concern from my publisher about choosing recognizable names of artists and designers, but I was mindful of how exclusionary and biased the system of art/design canonization is. This led to some important discussions about how to produce a selection of art/design works and recipes. I was concerned about reinforcing the canon that I ultimately wanted to address systemically.

Beyond these issues, there also had to be a conceptual relationship between the dish and the method(s) used by the artist or designer. In terms of determining the still life photographs, they were approached as improvised sculptures, largely determined by the scarce amount of film, props and food I had on hand.

Quiche Haring features a yeasted dough of a Pennsylvania Dutch onion pie, a nod to his roots growing up in rural Pennsylvania, flecked with poppy seeds, sesame, caraway and onion of the iconic New York “everything” bagel. Speaking to the ways she used economical ingredients in her depictions of highly collectible artists, in Choi’s interview at Archestratus, she mentioned that she used onions in this still life because she just happened to have them in her pantry that day.

Quiche Haring features a yeasted dough of a Pennsylvania Dutch onion pie, a nod to his roots growing up in rural Pennsylvania, flecked with poppy seeds, sesame, caraway and onion of the iconic New York “everything” bagel. Speaking to the ways she used economical ingredients in her depictions of highly collectible artists, in Choi’s interview at Archestratus, she mentioned that she used onions in this still life because she just happened to have them in her pantry that day.

In your intro, you mention that the “rituals of food consumption…are a seismograph of privilege.” How does Le Corbuffet work as a critique of contemporary food culture?

It does, and it doesn’t. In considering food’s relationship to privilege I tried to keep things accessible from an economic and technical perspective, which is the point of the entire project — to encourage the reader to see ordinary implements and ingredients as creative tools. There are aspects of food culture that were unavoidable to contend with, such as the excessive packaging of foodstuffs, or bruised and imperfect produce, the cost of making a meal, the economic values informing food photography, and so forth. There is a political dimension to all of these things, which I had to take up, because I am operating within this space of production.

However, there are myriad issues related to food production that this project doesn’t address: the relationship of meat to socioecology, gendered labour, the food supply-chain, and so forth. (These would be different projects.)

Lucy Orta Torta takes cues from the “tent-like, inhabitable sculptures” of the artist and encourages home cooks to experiment with the architectural possibilities of pastry.

Lucy Orta Torta takes cues from the “tent-like, inhabitable sculptures” of the artist and encourages home cooks to experiment with the architectural possibilities of pastry.

You also encourage people to improvise with the recipes—why is this important?

As “scripts”, I was interested in the parallels between process art, Fluxus scores, and recipes. I consider the recipes as prompts for encouraging arte-vita, of producing art in the everyday. Recipes are inherently rubrics for producing iterative but not exact copies, an act of postproduction based on an imaginary original, so I tried to prompt the reader/ participant to suffuse the process with their own subjectivity and preferences. My hope was that their detours would lead to new creations.