Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

All over the world many communities are tentatively taking their first steps to heal from the past year of COVID-19, where public health, well-being and the economy have been hugely affected— not to mention rising unemployment, food insecurity and climate change, all of which have been brought to the forefront of concerns and decision-making worldwide. In a recent article exploring recovery plans for our cities on SPACE10, Steph Wade writes that 2021 should be the year we “begin to overhaul the systems that have existed as our societal foundations for decades”. While returning to normal is a phrase dominating the news at the moment, many believe it is in fact the very antithesis of what we need to rebuild the health of our citizens, the economy and the planet.

This, in brief, is how the city of Frankfurt decided to approach rebuilding their city after the devastation of World War I and the resulting economic depression. The housing crisis in German cities sparked the ambitious initiative known as The New Frankfurt, or Das Neue Frankfurt. This initiative aimed to regenerate and improve urban space, and thus residents’ lifestyles, with affordable public housing and modern amenities. Das Neue Frankfurt was also the name of the monthly magazine which publicized the program to subscribers around the world— as well as the latest trends in urban design, art and education— and eventually led to attention from other governments seeking modernization of their cities. The program was led by a team of architects hired by Ernst May, the director of Frankfurt’s Municipal Building Department. Of this team of architects there was only one woman, Margarete “Grete” Schütte-Lihotzky, who would design what came to be known as the Frankfurt Kitchen.

THE NEW FRANKFURT AND STANDARDIZED LIVING

Born in 1897, Margarete Lihotzky was an Austrian architect, and later an instrumental activist in the Austrian resistance to Nazism. After studying at Vienna’s School of Applied Arts, she started to plan affordable settlements for World War I veterans in 1926. This caught the attention of May, who was, at the time, the city architect of Frankfurt and a somewhat utopian thinker with a focus on improving urban housing and environments for working class communities.

Key characteristics of the New Frankfurt housing estates were the flat roofs and standardized forms1 — modernist cubes that contained compact but functional living spaces with the aim of making day-to-day life easier and more efficient for residing families.

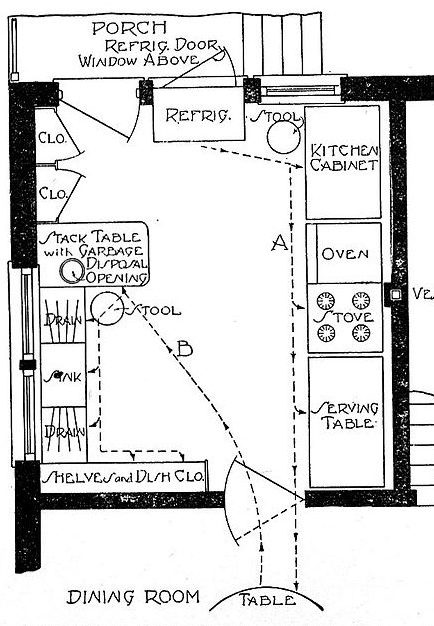

Within these apartments was Lihotzky’s kitchen design, which MoMA hails as a “rational, unpretentious, and socially oriented” space. The first standardized kitchen of its kind, each space came with the same appliances and furniture: a swivelling stool, a gas stove, a foldaway ironing board, an adjustable ceiling light, a removable garbage drawer and built-in storage bins. The design was neat and compact, but also made the tasks of cooking and cleaning up accessible and efficient. The labelled aluminium storage bins could be pulled out, with spouts to pour ingredients. Materials were chosen carefully, with oak used for flour containers (to repel mealworms) and beechwood for surfaces (to prevent staining and knife damage).

- The Frankfurt Kitchen, MoMa.

Before the 20th century, kitchens were only really present as workspaces in homes that had household staff2. There was no standard design to a kitchen like we know today. However, as the war had wiped out accrued wealth and the ability to afford household staff, advertising and product inventions shifted their focus to a new customer— the housewife. With the goal of making domestic life easier for women, the innovations made to kitchens in the 1920s were classed as feminist advancement.

HOUSEHOLD ENGINEERING AND EFFICIENCY

Lihotzky, aiming to unchain women from the gendered struggles of poorly designed kitchen spaces, took inspiration from the efficient, yet narrow kitchens of railway dining cars as well as the work of Christine Frederick. Frederick was a home economist of the early 1900s who worked to improve efficiency in women’s chores with her own Home Experiment Station. The Experiment Station investigated different methods for improving labor-efficiency in the kitchen— the findings of which were published as a book in 1919, titled Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home.

2. “The Frankfurt Kitchen Changed How We Cook— And Live”, Sarah Archer.

Lihotzky, like Frederick, carried out extensive time-motion studies inspired by Taylorism— a system of scientific management created by Fred W. Taylor to improve performance in factories. Although the approach of the Frankfurt Kitchen was centered around easing the load of women’s labor around the home, perhaps taking inspiration from intensive factory management (designed by a man) was not the best way to achieve liberation from daily housework. In Culinary Turn: Aesthetic Practice of Cookery, Anthonia Surmann argues,

“The design of the ‘Frankfurt Kitchen’ was indeed based on an emancipatory approach, but ultimately this demand could not be implemented as the crucial characteristic of professional occupation – remuneration – was not part of it.”

Moreover, the compact and narrow nature of the Frankfurt Kitchen isolated women from the rest of the family, and by its very nature suggested all housework would be carried out by them, alone.

However, Lihotzky did achieve her goal of creating a cooking space that was central to apartment living— not necessarily in position but in priority of use— writing in 1926 that “the arrangement of the kitchen and its relationship to the other rooms in the dwelling must be considered first.” A sliding door connected the kitchen to the living area, and as all distances were meticulously measured, the distance from kitchen to dining table was set at three meters. Lihotzky’s design provided what was, overall, the first functional, considered space that housewives had seen designed for them and their day-to-day lives.

The success of the New Frankfurt model and the ideal apartment living it presented caught the attention of other countries. In 1930, the Soviet Russian government asked Ernst May’s team to plan new modern towns in the Soviet Union. Following this, the French housing minister commissioned 260,000 kitchens inspired by Lihotzky’s design principles.

DESIGNING FOR COMMUNITY AND RECOVERY

As you may have predicted, the rise of the Nazi regime and WWII halted the New Frankfurt developments, and Margarete Lihotzky was actually imprisoned during the war for fifteen years due to her activist efforts against Nazism, narrowly escaping a death sentence (Graphis, 2001).

But Lihotzky lived an incredible life, until she died in January 2000 at the age of102. Her obituary in Graphis, 2001 (Vol. 57, Issue 331) tells us more:

“In 1938 she took a position at the Academy of Fine Arts in Istanbul and designed school buildings, becoming a member of the Communist party in the late ‘30s…In 1946 she returned to Austria, but her Communist Party membership prevented her from getting many architectural assignments during the Cold War…In 1988 she was offered the Austrian Medal of Science and Art, but declined it because of the alleged Nazi affilitions of Kurt Waldheim, Austria’s president at the time.”

Lihotzky and the rest of May’s architectural team, designed a way for cities to recover from the trauma of a World War and depression. Thinking of citizens’ needs and desires first, The New Frankfurt transformed urban living and made daily tasks modern, accessible and affordable for their time. The egalitarian design principles of Lihotzky’s kitchen design (and in fact her other architectural projects) can provide a springboard for how we design a way out of this post-pandemic limbo.

The Frankfurt Kitchen focused on efficiency, yes, but did not ignore the economic and social changes that had taken place due to the War. Referencing Steph Wade for SPACE10, our post-pandemic design strategies should be “prioritizing sustainable, circular principles”, making our cities more resourceful and desirable places to be. Redesigning the kitchen now does not simply require an overhaul of standard architectural practice, but also the adaptation of everything right down to the methods and materials we use in the kitchen.

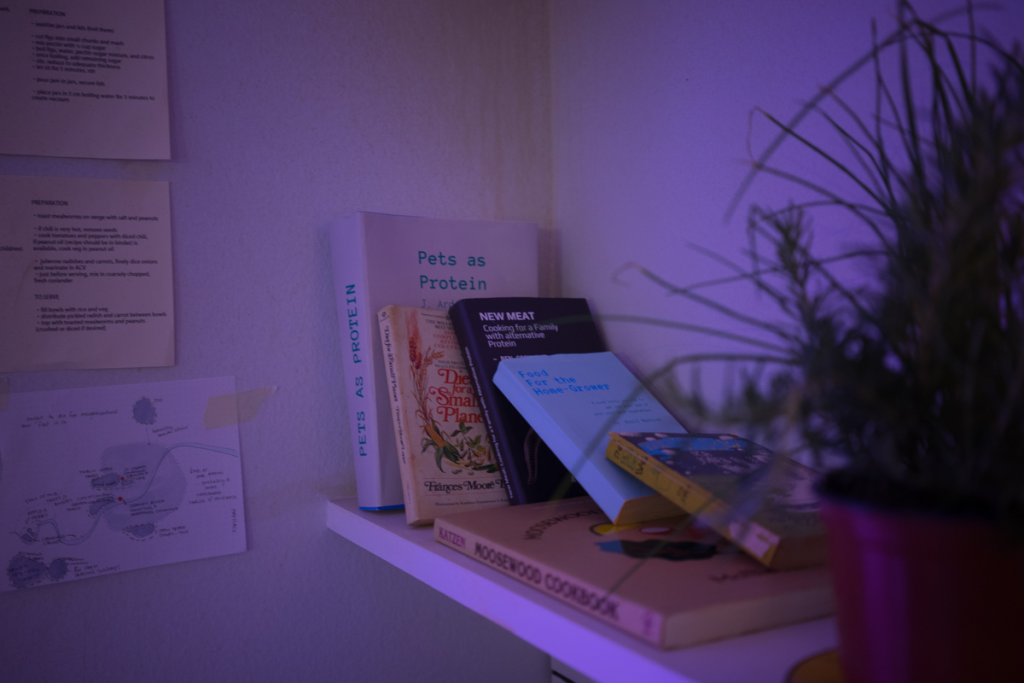

As we consider the design implications presented post-pandemic, I am reminded of Superflux’s experimental installation Mitigation of Shock, a doomsday-esque imagining of a London apartment in the year 2050. However, SPACE10’s manifesto is much more optimistic, promoting a form of “hedonistic sustainability” (coined by Danish architect Bjarke Ingels) that creates pleasurable, even playful, environments for users. Perhaps this is the first step to rebuilding our economies and lifestyles, designing healthy and sustainable cities, and beginning the road to recovery for our planet.