Repast tells the stories of cooks, designers and scientists throughout history to help us design better food futures.

We are certainly no strangers to the self-taught nutritionist, with new products seemingly appearing from the ether that promise to cleanse, to provide flatter stomachs or just to improve overall health. Many of us have fallen prey to the false theories behind “skinny teas”, juice cleanses and new, bizarre eating habits, but one thing has changed. Whilst it was previously those of ill health, the vulnerable or impressionable that would fall victim, now social media, celebrity influencers and deceptively friendly branding make it difficult to determine legitimacy amongst these hoaxes.

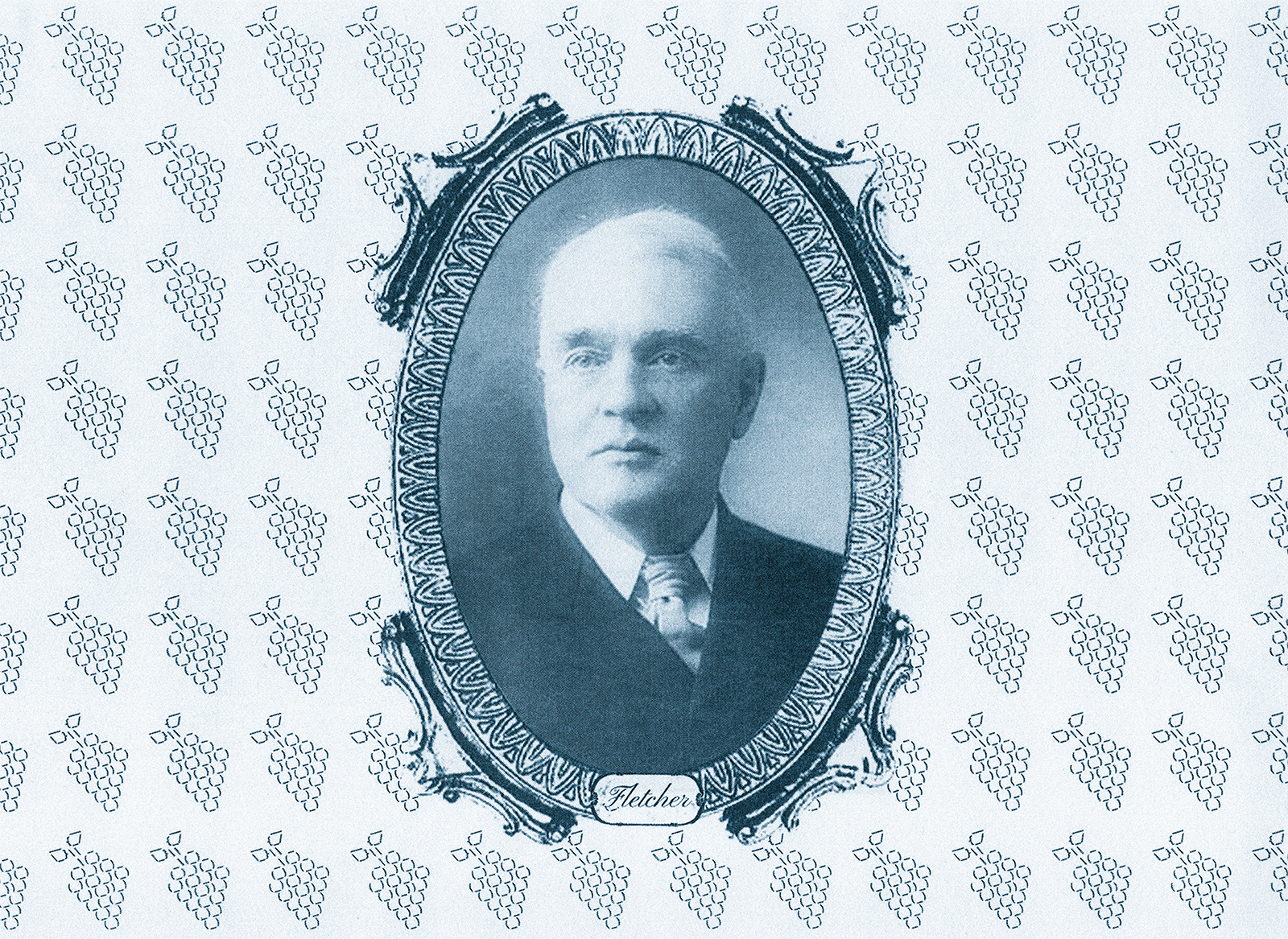

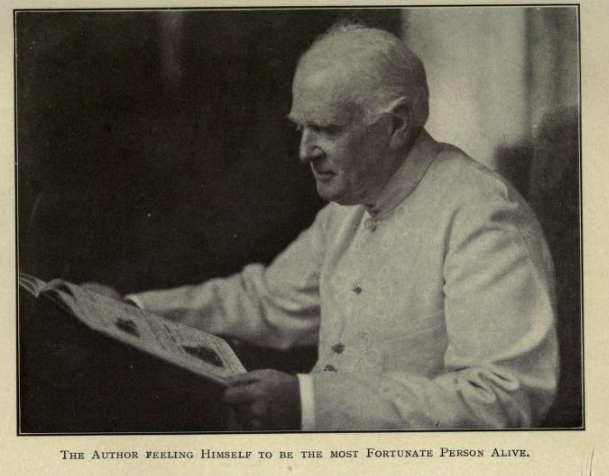

Although spurred on by the internet in recent years, food faddism is not a modern invention. In the early 1900s Horace Fletcher, a man of multiple professions from Massachusetts, began promoting what he titled Fletcherism — the practice of chewing one’s food into a “creamy substance” with no remaining taste to combat obesity and other health problems. His claims, although popular at the time, were of course founded without any scientific evidence, and Fletcher used his own health and weight transformation to advertise the strange idea to the masses, writing multiple publications on the topic. For example, Fletcher’s The New Glutton or Epicure published in 1903, “confirms” the author’s claims, stating:

“The author still claims discovery of a distinct physiological function which he first named ‘Nature’s Food Filter.’”

Horace Fletcher’s obsession with mastication may seem comedic to us now, but can be used as a means to explore the importance of sound research and evidence in new food products, routines and systems. Fletcher, who was, essentially, an influencer of the Edwardian era, sold his weight loss secrets similarly to the way that Goop sells controversial wellness fixes. His story serves as a case-study on how new-fangled fads can quickly take over a generation of consumers looking to improve their health, or even social status.

Fletcherism, What It Is

In “Fads—Fanciful, Foolish, and Suicidal” in Diet and Die (1935), public health educator Carl Malmberg introduces the reader to the idea of food fads being “generally the work of some fakir who has lifted an idea out of thin air” but that “the promoter of the fad offers the idea as the most important discovery in years”. Malmberg then uses Horace Fletcher as a case study to illustrate the poor scientific backing and the damage that these crazes cause to public health. He suggests that Fletcher actually died as a result of the “toxemia” caused by his eating behaviors—although it is widely understood that he died from a case of bronchitis at the age of 69.

It is no surprise that Fletcherism and its founder received such criticism, as the fanatical approach to eating prescribed readers with advice such as “get all the good taste there is in food out of it in the mouth, and swallow only when it practically ‘swallows itself.’’” (Fletcher, c.1913) This wasn’t all, as the third step in a five-step approach, this mandate was accompanied by others which included “wait[ing] for a true, earned appetite” and not to “allow any depressing or diverting thought to intrude upon the ceremony”.

Restrictive fad diets may be short-lived in popularity, but have long-standing results—the devaluation of our emotional relationship with food instead of the recognition of its integral role in the way we connect and share, experience pleasure or even alter our moods.

Fletcher, a man who had spent his life pursuing multiple careers from an artist to an opera house manager, found himself plagued by ill health and obesity in his mid-life. In the chapter “How I Became a Fletcherite” in Fletcherism, What It Is (c.1913), the author admits that he was turned down for life insurance at the age of 40, and so became determined to “save myself from my threatened demise”. When called to Chicago on business, Fletcher found himself with free time in the city, which he dedicated to taking up “the careful study of Taste”. A first-time reader might imagine that this involved eating the most decadent food available, exploring new cuisines and jotting down the sensations in a notebook—but Fletcher instead began to study the motions of chewing, and credited himself with the discovery of what he called the “food-gate” or “Nature’s Food Filter”—which we now know is the involuntary reflex of swallowing.

It is most likely that Fletcher’s personal success with his methods can be attributed to the tedious nature of excessive chewing and its correlation with longer mealtimes and smaller portions, rather than the actual act of mastication. Nevertheless, Fletcherism received attention in the media just as intended, and was even apparently adopted by King Edward VII of England. The movement became more palatable to the public, although its following were mockingly nicknamed “the chew-chew cult”.

“On my fiftieth birthday I rode nearly two hundred miles on my bicycle over French roads, and came home feeling fine. Was I stiff the next day? Not at all, and I rode fifty miles the next morning before breakfast in order to test the effect of my severe stunt.” – Horace Fletcher

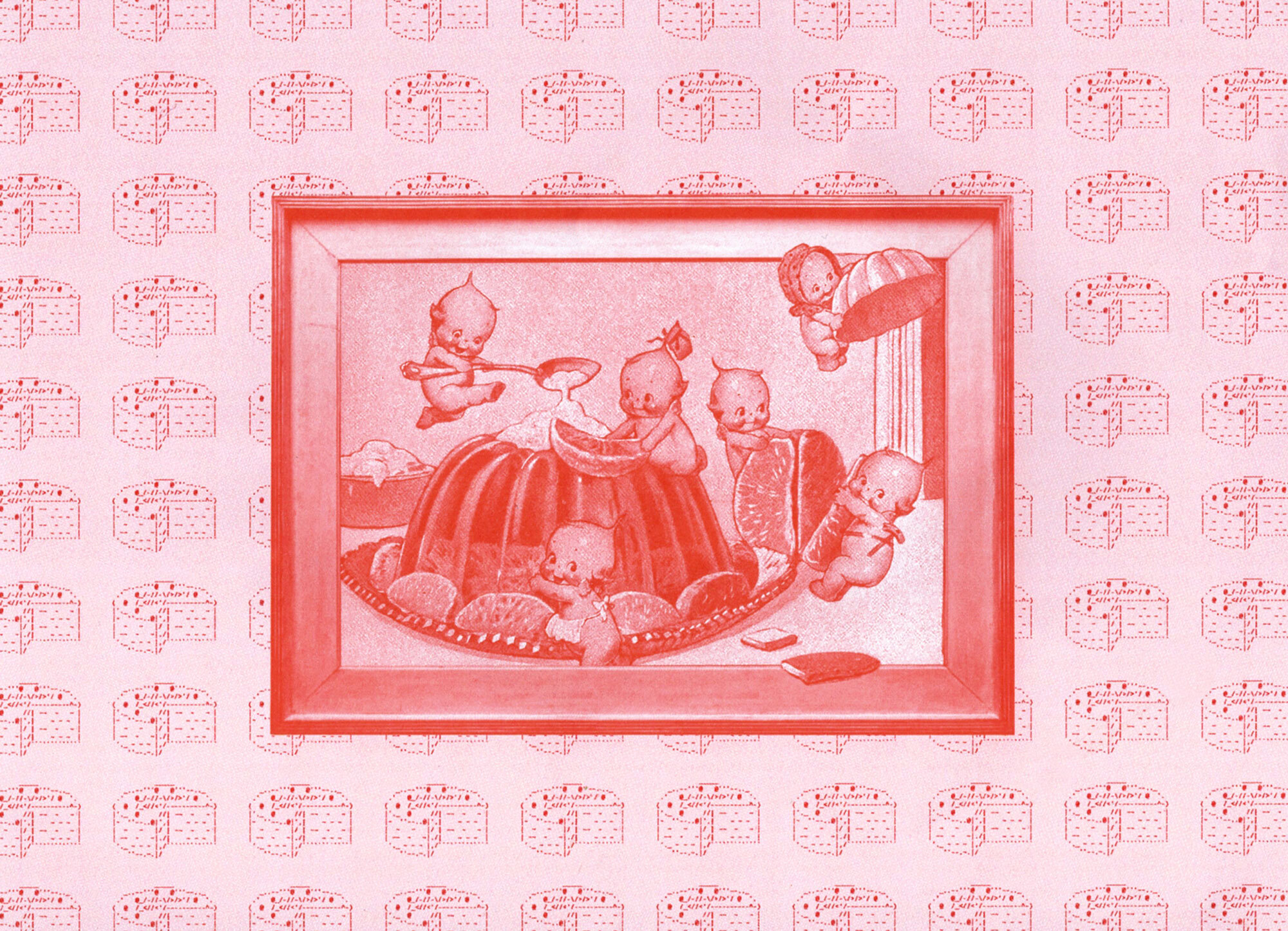

Despite his self-proclaimed transformative health, Fletcher died in 1919 after a long illness, just a few years after publishing his book summarizing Fletcherism. His obituary in The Baltimore Sun, pictured below, hails the writer as an expert on dietetics and highlights his academic achievements including an experiment in which he survived on a diet of just potatoes for 58 days to prove that it did not affect his health.

The Forerunner of Fads

While it shouldn’t be ignored that Horace Fletcher was, for his time, a pioneer of dietetic research, and “Fletcherizing” did receive great reviews and media attention, his promotion of an extremely unnatural behaviour as a solution to ill health was a forerunner of the food fads we see today.

Fletcherism was an essentially liquid diet which resembles the numerous modern regimes promoted to, mainly, women today (think juice or broth cleanses that promise to “detoxify”). In fact, today, obsessive behaviors such as counting calories or excessive chewing are associated with eating disorders , and are often promoted as weight loss tactics in clandestine online ED communities. Fletcher’s obsession with what entered (and in addition, what exited) his body would actually support present day mental health advice which suggests that enforcing rules on one’s eating rituals is a surefire way to make food an enemy.

In Diet and Die, Malmberg states that the victims of food fads are often in ill health and desperate for a cure, willing to believe that this one lifestyle change holds the key. If we look at Fletcherism through this lens, Fletcher was perhaps a victim of his own making. Our knowledge of our bodies’ responses to caloric intake, healthy lifestyles and the importance of balanced diets has advanced massively since the age of the “chew-chew cult”. However, our emotional and mental relationship with that information is still not there. The importance of verified nutrition information and reassurance around a more intuitive way of eating has never been greater, in an age of constant product inventions and influencer marketing that can sway even the wisest and most weathered consumer. Restrictive fad diets may be short-lived in popularity, but have long-standing results — the devaluation of our emotional relationship with food instead of the recognition of its integral role in the way we connect and share, experience pleasure or even alter our moods.